Bay Area Homelessness

Until very recently, homelessness was considered the problem of individual cities and counties. For a metropolitan region like the Bay Area, which is divided into nine counties and 101 cities, this approach fails to meet the needs of an intraregionally mobile homeless population. In this report, a regional lens provides a new perspective on the homelessness crisis and offers new ways to address the problem.

Executive Summary

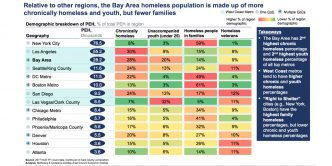

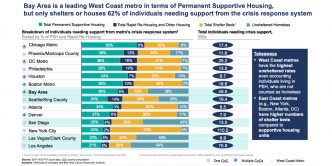

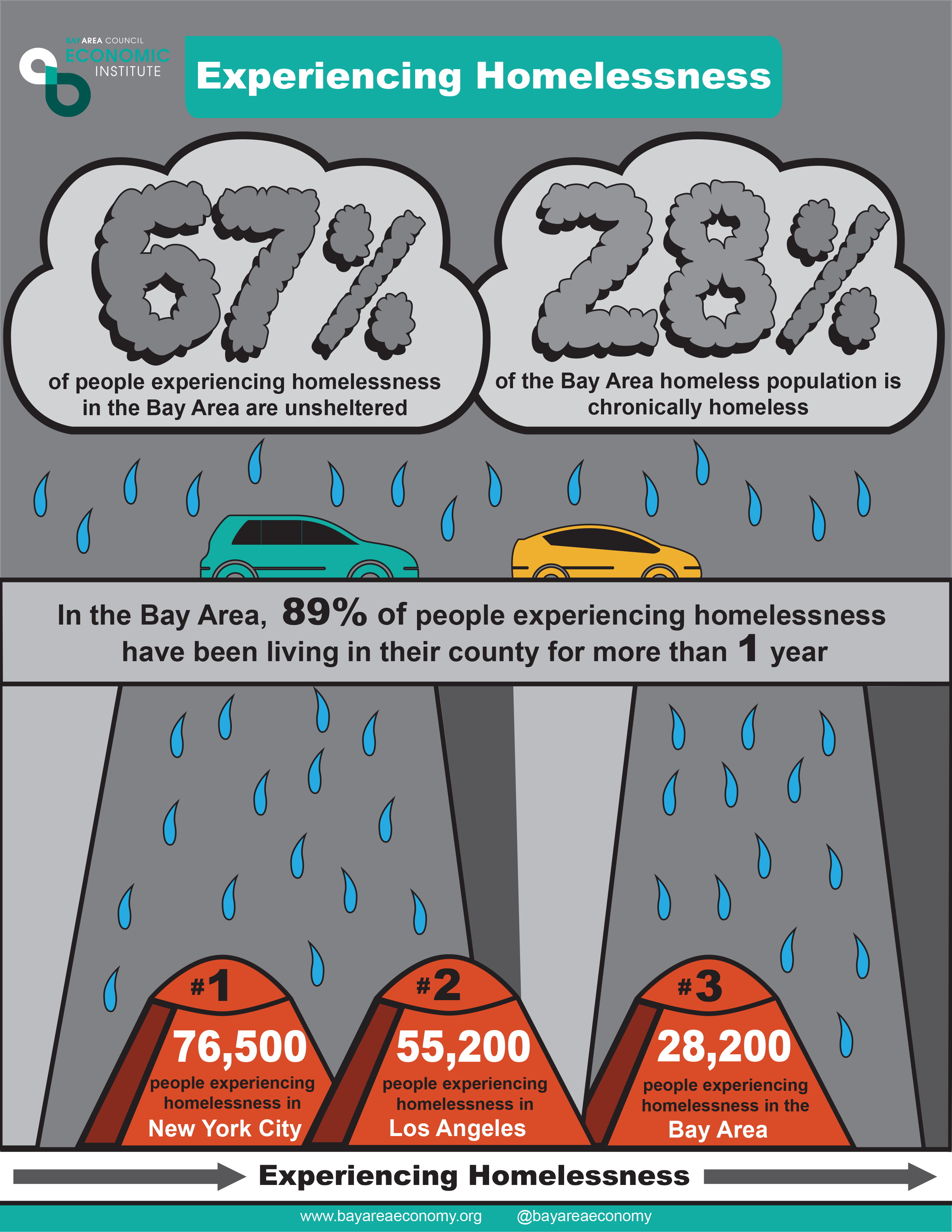

By virtually every measure, the Bay Area’s homeless crisis ranks among the worst in the United States. The Bay Area has the third largest population of people experiencing homelessness (28,200) in the U.S., behind only New York City (76,500) and Los Angeles (55,200), according to Point-in-Time counts. The Bay Areaalso shelters a smaller proportion of its homeless (33 percent) than any metropolitan area in the U.S. besides Los Angeles (25 percent), making the crisis highly visible across the region. The absolute size of the Bay Area’s homeless population, combined with the region’s dearth of temporary shelter options and an insufficient supply of supportive housing, desensitizes the public and condemns the homeless to lives of hardship.

According to the 2019 Bay Area Council poll, residents of the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area rank homelessness behind only housing affordability (which is closely related to homelessness) and traffic congestion as the region’s biggest challenges, and the number of residents who believe homelessness is the region’s top problem has nearly tripled since 2015.

Despite progress on several fronts, a solution to the crisis remains elusive. Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo have pioneered the use of cabin communities and tiny homes, respectively,

to keep homeless communities intact while providing shelter and services. In San Francisco, Mayor London Breed launched the Rising Up initiative to provide housing subsidies and job placement services to more than 500 young people experiencing homelessness. Santa Clara County is recognized statewide for having developed the most transparent analyses of its existing homeless services. San Francisco has added large numbers of permanent supportive housing and rapid re-housing beds in the last five years, and has more supportive housing per resident than any other U.S. city.

The private sector has also been increasingly engaged. In 2018, Kaiser Permanente announced $200 million to fight homelessness nationwide, with the first project being the $5.2 million acquisition of a 41-unit housing complex in East Oakland that will be rented to low- income families. In Santa Clara County, Cisco has committed $50 million to build more housing, improve technological capacity, and scale promising programs.

Yet between 2011 and 2017, the number of people experiencing homelessness in the Bay Area slowly grew. This trend occurred even as the region was growing its inventory of homelessness support assets, including permanent supportive housing units and rapid re-housing programs. While jurisdictions have been successful in moving more homeless individuals and families into stable housing, a larger number of people are experiencing homelessness for the first time.

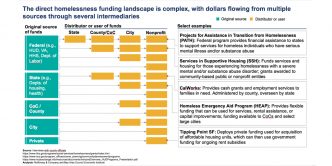

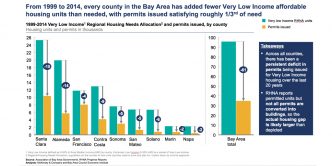

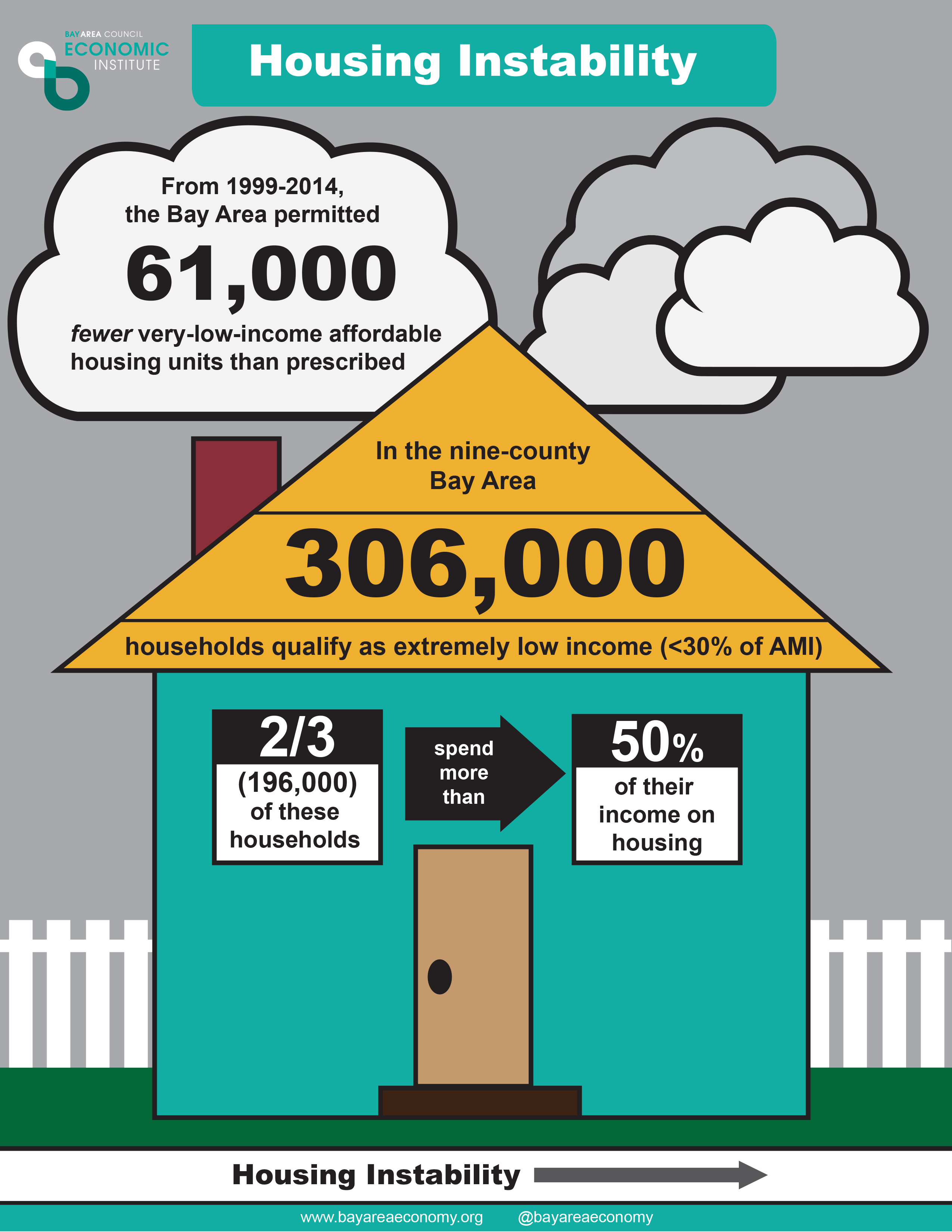

The Bay Area’s chronic housing shortage especially at extremely low-income levels, limited growth in wages at the bottom of the income spectrum, an insufficient inventory of short-term shelters and permanent supportive housing, and too few resources for mental health and addiction services, each played a role in leading up to the current crisis. Complex funding streams tied to specific populations or uses also make a solution difficult to attain. Federal funding programs have prioritized permanent housing solutions as the most effective path to ending homelessness. As such, the inventory of temporary shelters and other emergency options for shelter in the region has fallen.

Faced with the combined shortage of deeply subsidized housing units and short-term shelters and transitional units, the majority of the region’s homeless population goes unsheltered each night. This dynamic has forced Bay Area cities and counties to grapple with homelessness on dual fronts. They must balance the immediate need to address the humanitarian crisis on their streets and in homeless encampments, while also focusing on the longer-term solution to homelessness: providing a home to every individual and family.

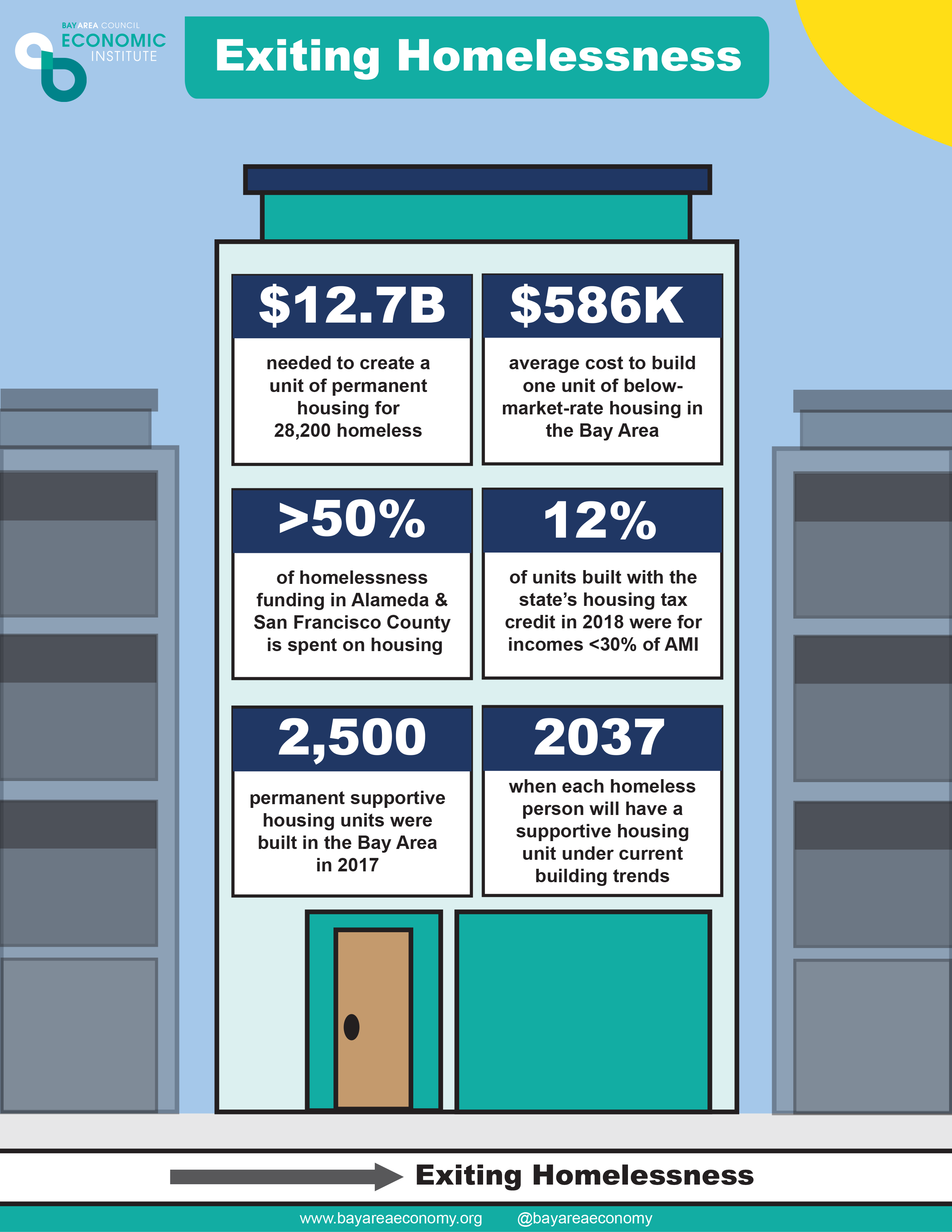

This balance is necessary because providing permanent housing to every person experiencing homelessness will take many years under the status quo. Given existing growth rates in the inflows into homelessness and assuming the region could sustain 2017’s annual increase of permanent supportive housing units (2,500), the Bay Area will not be able to provide a bed to each of its homeless residents until 2037. But even that projection is optimistic given that Point-in-Time counts only reflect the homeless population on a single night. An actual solution might be much further away.

Until very recently, homelessness was considered the problem of individual cities and counties. For a metropolitan region like the Bay Area, which is divided into nine counties and 101 cities, this approach fails to meet the needs of an intraregionally mobile homeless population. For instance, the Bay Area’s myriad datasets on homelessness are incompatible, and assets are planned and built without coordination or optimization. Problems in one community spill into another. According to Jeff Kositsky, Director of San Francisco’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, “Homelessness in San Francisco will never be solved as long as the city is surrounded by 15,000 unsheltered homeless people in the neighboring counties.”

Solving the Bay Area’s homelessness crisis requires interventions across all stages of homelessness:

-Preventing individuals from becoming homeless is a cost effective way to keep the crisis from growing.

-Providing accommodation to the unsheltered homeless residents who currently have no place to go will alleviate the crisis on the region’s streets.

-Maximizing the number of units and housing programs dedicated to homeless individuals and families will provide a long-term solution.

Successfully offering interventions across this spectrum will require additional resources to expand the region’s inventory of support assets, as well as policy reforms at the local, regional, and state level to optimize existing programs. In this report, we use regional data to support policy recommendations in three categories:

Stem new inflows into homelessness and increase exits. Addressing homelessness at its earliest stages requires more effective diversion and prevention programs to keep individuals and families in their homes. An expanded housing supply available to extremely low-income households can be achieved through incentives targeted to units reserved for households earning between 0 and 30 percent of area median income. More work must be done across counties to understand and meet the existing and projected accommodation need.

Drive greater state and regional collaboration. For instance, the state could play an active role in homelessness solutions by consolidating its efforts into a State Homeless Services Agency that can offer flexible funding for housing construction and services. The agency can condition funding on the creation of regional homelessness management plans that standardize definitions for monitoring and tracking homelessness data and trends.

Simplify and improve homeless services. Private and philanthropic capital can be deployed in innovative ways, from testing the effectiveness of interventions with Pay for Success programs to using technology to streamline services. Regional task forces on funding and technology can identify gaps in existing funding sources and design platforms for intake, care, and tracking.