Strategies for Bringing Down Pharmaceutical Costs (Australia, Canada, Norway et al.)

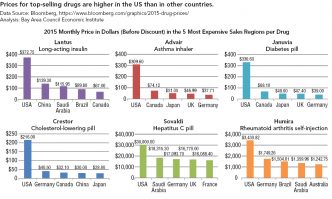

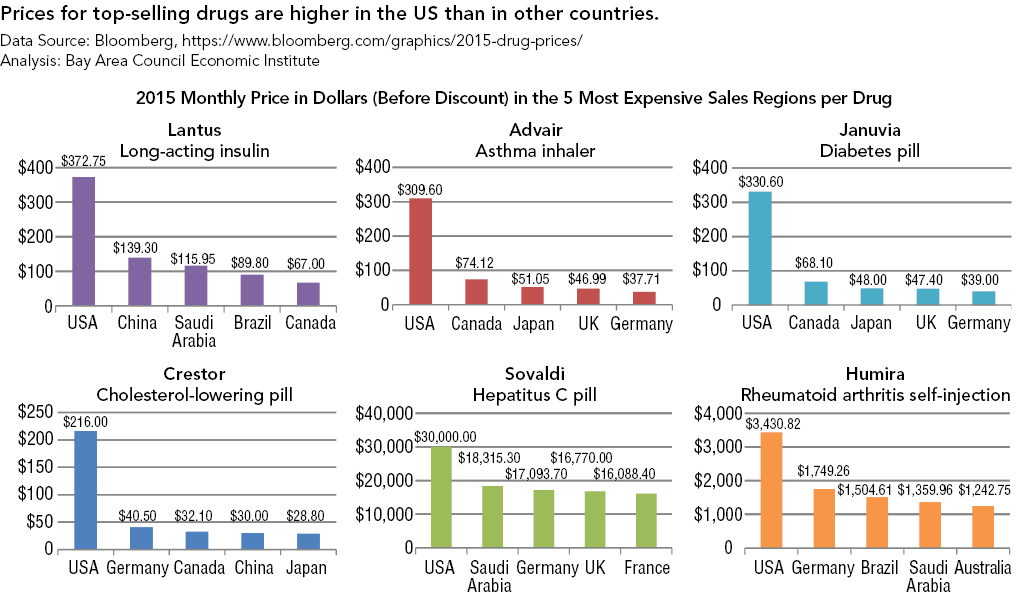

The governments of virtually every country in the world except the US both negotiate prices with drug companies and maintain technology assessment offices to gauge the added medical benefit, if any, that the introduction of a new drug could deliver. The National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) in England and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) in Australia are among the best known of these institutions that decide which drugs are approved for use and for reimbursement. For example, NICE declined at first to include on its formulary two cholesterol-lowering drugs, Amgen’s Repatha and Sanofi’s Praluent, but later reversed its decision after reaching agreements with the manufacturers to receive additional discounts off their list prices.14

The United States government has moved away from technology assessment within the public sector since the Office of Technology Assessment was shuttered in 1984 on the grounds that it hampered innovation. Though there are a number of influential health technology assessments, they are independent. The Secretary of Health and Human Services is explicitly prohibited from negotiating with drug makers on behalf of the entire Part D program (Medicare’s prescription drug benefit), but manufacturers negotiate prices with Part D plan sponsors that act as private contractors for the program. Other US purchasers, such as the VA and state Medicaid programs, have statutory access to lower prices for drugs and can command supplemental rebates in order to reflect the relative value of a particular drug.

Other countries, including Germany, Spain, Italy, and Canada, have used reference pricing to try to grapple with the issue of pharmaceutical costs at odds with value without crimping innovation. Under reference pricing, drugs that have identical or similar therapeutic effects are grouped into classes, and the insurer pays only one price (the reference price) for all drugs in that class. If a drug company is charging more than the reference price for a drug in that class, and a consumer wants to use that more expensive drug, the consumer pays the difference. This approach raises a number of issues in theory which are borne out in practice: where to set the reference price relative to a group of drugs, which drugs are truly novel and “out of class,” and how to decide the classification groups of pharmaceuticals to start with.15 Yet the results are worth paying heed to—a study published in The American Journal of Managed Care found that the use of four reference pricing policies (in Germany, Norway, Spain, and Canada) was associated with decreases in the price of the target drug classes ranging from 7 to 24 percent.16but the principle is useful as well for some medical devices and procedures that can be easily grouped in a class and priced.

Another promising approach with an international component would be establishing reciprocity with drug-approval agencies in other developed countries so that drugs that have been approved overseas and have yet to receive FDA approval could get expedited approval in the United States. As former FDA official Henry I. Miller writes, this would involve “routine, automatic ‘reciprocity’ of drug and medical-device approvals with certain of the FDA’s foreign counterparts, so that an approval in one country would be reciprocated automatically (subject to the creation of approved labeling, etc.) by the others. That would make more drugs available sooner in the United States (and other participating countries), increase competition, and put downward pressure on prices. Availability is critical, because if a drug is not available, then price is irrelevant.”17

Reciprocity would be a more substantial change in policy than the reimportation ideas that have won bipartisan favor in the past, but it could also result in a much greater impact on prices and on choice. Challenges would involve patent protection issues, the impact on domestic markets of potential US demand, and the danger that the regulatory process would be lax in some countries and jeopardize the health of Americans.18

Paring Back Overuse of Medical Technology (Japan)

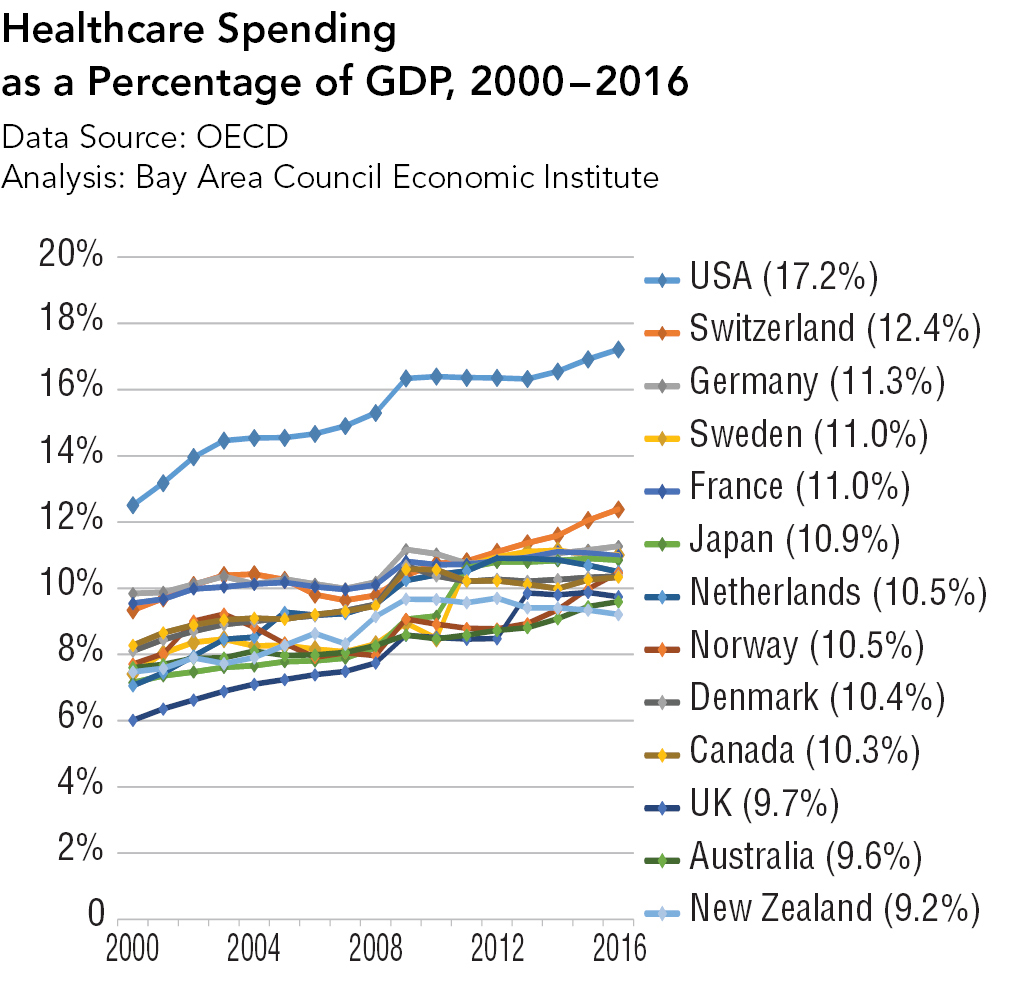

Americans’ heavy and early use of new medical technologies, abetted by early reimbursement by insurers, is another key factor in higher US health costs. For instance, proton beam therapy aimed at shrinking tumors has been a huge growth area despite little or no evidence that it yields better outcomes than traditional radiation treatments. By 2018, there will be four proton beam machines in Florida, three in Washington, DC, and two in Oklahoma City, compared to a single machine in Canada.19

There are ways to scale back the heavy use of new technology without seriously inhibiting the incentives that prompt inventors and entrepreneurs to bring new potential breakthrough technology to the market. For instance, Japan actually has more privately-owned MRI (magnetic-resonance-imaging) machines per capita than the United States. However, per capita spending in Japan on MRIs is less than in the US.

Why? One reason is reimbursement policy. Unlike the US, the Japanese government reimburses only a fraction of the original price per procedure for multiple MRIs performed on the same body part of the same patient. Other countries practice a form of bundled pricing in which the cost of scans must fit into an overall patient budget. Japan, to be sure, has been taken to task by other countries for its supposed profligacy toward imaging costs, but adopting even a version of its market-friendly approach toward technology would bring down US costs.20