Impact investing bridges the divide between philanthropy and traditional investing practices, bringing private capital to bear on social issues while generating financial gains.

Because impact investments can cut across asset classes and can have a wide range of financial return expectations, it can be difficult to categorize impact investments under one single umbrella. Through a survey of a broad range of impact investors, JP Morgan and the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) have estimated that the overall impact investing industry grew to $60 billion of invested capital in 2015, much of which is invested through private equity and venture capital funds.

Given that this amount represents only a small fraction of global investment activity, many stakeholders from multiple sectors have worked to draw more mainstream capital into the field as a way to simultaneously make profits while addressing global needs. Industry estimates suggest that the impact investment market could reach $400 billion to $500 billion in just a few years, providing a significant amount of capital to drive new market-based solutions to social and environmental issues in both the developing and developed world.

Classifying the Social Returns to Impact Investing

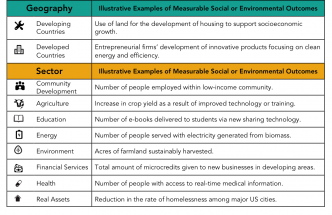

Impact investments can span a wide variety of asset classes and geographic focuses, but their social impact targets can generally be grouped into three areas:

- Creating social value through new products or services – Probably the most common theme for impact investors is to organize around an issue area. Common impact objectives include, but are not limited to: sustainable agriculture and food systems; financial inclusion for marginalized individuals; educational opportunities; expanded access to low-cost health services; conservation of natural resources; clean energy; climate change mitigation; and access to safe drinking water.

- Generating new employment opportunities for disadvantaged populations – While new products can create new opportunities, the companies producing these products do not always employ local workers. Microfinance investments are a classic example of providing small enterprises with an ability to scale and grow. Other investment types have targeted growing companies that employ low-income or low-skilled workers.

- Investing in specific geographies – There are impact investors that will look to grow companies within specific economically disadvantaged areas of the globe, but more often, geography-first impacts are made through investments in real assets. This often comes in the form of housing, through international property funds or domestic low-income housing tax credits.

Classifying the Financial Returns to Impact Investing

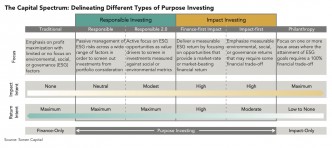

Early research in the impact investment field pointed to two distinct groups of investors—those whose investment philosophy was “impact-first” and those that were “finance-first.” Impact-first investors seek to generate social or environmental returns and are often willing to give up some financial return if needed— these investments are said to yield concessionary returns. Finance-first investors are typically commercial investors who seek market-rate returns while achieving some social or environmental goals. These investors might look for commercial products that add social or environmental value (e.g., solar lanterns in developing countries) or they might respond to tax policies that provide subsidized returns for certain types of investments that otherwise provide below market-rate returns (e.g., for affordable housing in the U.S.).

This separation, while still useful in thinking about the range of investment options, does not necessarily mean there is or should be an impact-return trade-off in all impact investments. In fact, two recent studies have found that impact investment funds that target marketrate returns perform similarly to traditional private equity and venture capital funds:

- In 2015, Cambridge Associates and GIIN launched the Impact Investing Benchmark. For funds launched since 1998, the Impact Investing Benchmark yielded an internal rate of return of 6.9%, versus 8.1% for comparable traditional funds

- A 2015 survey of 53 impact investing private equity funds conducted by the Wharton Social Impact Initiative sought to enumerate the extent to which fund managers will sacrifice mission in exchange for financial returns. These funds yielded approximately a 13% return (both realized and unrealized) between 2000 and 2014. This rate of return is nearly identical to the two benchmark indices used—the Russell Microcap/Russell 2000 index and the S&P 500.

Bringing Impact Investing to the Mainstream

New benchmarking of financial returns for impact investments has begun to move the industry away from the zero-sum thinking that financial returns had to be traded for social returns. However, many structural constraints still limit the industry’s growth, and new investors to the field are still met with many questions and difficulties. These include:

- Preserving fiduciary responsibility while investing for impact

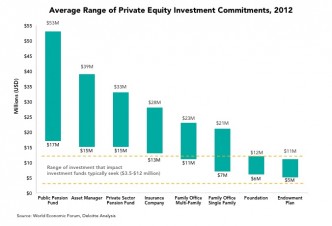

- Small scale of impact investment funds

- Insufficient fund track records

- Lack of fit within existing asset allocation frameworks

- Complexity of measuring social returns

Impact investment funds and the organizations that are thought leaders in the impact investing space, including GIIN, B Lab, and the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs, are playing a critical role as impact investing begins to filter deeper into the asset allocation philosophy of institutional investors and philanthropic groups. Impact funds—where the majority of impact investment dollars are placed—can begin to pull capital into the market in a more strategic way, and service providers—which are bringing some measure of consolidation to financial and social return data—have an opportunity to form more meaningful and powerful networks.

Government has also played a key role in building the impact investing industry into what it is today. Policies such as the Community Reinvestment Act and the institution of tax credit programs have created demand and incentives for targeted impact investments. Additionally, domestic governmental organizations such as the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and multilateral development banks on other continents have been making impact investments for years. Going forward, the public sector can continue to create synergies and alignment between many of the issues that are important to both impact investors and government.

The following list presents recommendations for structural adjustments in the impact investing field and changes to public policy—all of which would help to create a more robust market for impact investments.

1. Create better segmentation across impact investing funds

The continued misunderstanding around what actually constitutes impact investing has been perpetuated in part by the many funds that classify themselves as impact investors. In fact, these funds operate across a wide spectrum of investment philosophies. In the JP Morgan/GIIN survey, 55% of respondents targeted market-rate returns, 27% targeted below market-rate returns, and 18% focused on capital preservation. Each of these respondents falls under the impact investment category as it currently stands today—as each combines some aspect of social and financial return. However, the industry could create greater understanding amongst mainstream investors if it segmented itself in a more strategic way, separating those funds and investment opportunities that can generate returns comparable to other traditional investments from those that set out to trade financial return for social return.

2. Pool funds with similar investment and impact objectives

Small deal sizes and the need for enhanced due diligence continue to be limiting factors for the growth of the impact investing industry. To entice large institutional investors to make larger capital contributions, funds with overlapping investment philosophies and impact objectives should explore consolidation. Fund collaboration and partnership is not common practice today in the traditional investment space, as it would require fund managers to share some of their investment decision-making authority. What is more likely, however, is the creation of impact “funds of funds,” whereby large investments could be made into a larger fund that then makes many smaller investments into individual impact funds.

3. Agree to a common set of values and principles around impact measurement

While significant progress has been made through IRIS (Impact Reporting and Investment Standards) and GIIRS (Global Impact Investing Rating System)—two systems for measuring the social impacts of companies and investment funds—a more uniform system for measuring and reporting social and environmental impact is needed; until it is achieved, investors will continue to struggle with the meaning of social impact. According to the JP Morgan/GIIN survey, only 27% of respondents use the same metrics to measure social returns for all companies across the portfolio, and more than 30% track impacts through proprietary frameworks that are not aligned with external standards, like IRIS. It may be impossible to boil social impact down into a single number or metric, but there is an opportunity to report on a limited set of common measures for every fund without burdening fund managers and financial advisers with additional costs and duties.

4. Leverage the role of philanthropy in the impact investing space

Philanthropic investments can be used to help grow social enterprises (companies combining commercial and social goals) to a point where their business models and impact philosophies can be proven to traditional investors. They can also provide investment types that can catalyze more traditional capital to enter the market through loan guarantees or first-loss layered investments. Foundations making investments into social enterprises also complete extensive due diligence before placing their capital, which could be leveraged to lower due diligence costs for the entire impact investing sector. By utilizing existing impact investing industry networks, such as GIIN, impact investment data from foundations could be shared with mainstream investors in a way that disseminates best practices on deal-structuring, return expectations, and impact measurement.

5. Continue to revise public policies that can restrict the flow of capital into impact investments

Over the last few years, federal policies for foundations and pension funds have made it easier for capital to flow to impact investments. National policy should continue to be adjusted to bring more capital to bear on social issues, which could come in two forms:

- Provide greater clarity surrounding the requirements for impact investments to qualify for Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) credit. Currently, CRA investments need to be tied to geography, thereby making it difficult for large banking institutions to invest in impact funds that do not have a focus on a single domestic geographic area.

- Broaden the reach of the Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) Impact Fund. To qualify as an SBIC Impact Fund, impact funds must target 50% of their invested capital toward a distinct impact sector, economically distressed areas, early stage companies that have received federal awards, or energy saving investments. This limited menu of options disqualifies many impact funds that have broader impact philosophies.

6. Provide public sector investments alongside impact investments through innovative mechanisms

Innovative investment structures and public-private partnerships have been used most frequently to address domestic housing issues, with the New York City Acquisition Fund and the Bay Area TransitOriented Affordable Housing Fund providing best practices for the use of public funds to spur mainstream impact investment. These flexible structures utilize funding from government to reduce risk for mainstream investors.

The public sector can also catalyze investments in early stage high-impact companies through tax incentives for investors. Much in the same way that the Low Income Housing Tax Credit and New Markets Tax Credit have subsidized investments in low-income communities, similar credits could be offered to impact investors that make investments in early-stage companies that are hoping to create public benefit. In the UK, investors that make qualifying investments under the Social Investment Tax Relief program can deduct 30% of the cost of the investment from their income tax liability.

7. Create policy guidance to bring impact metrics into mainstream financial reporting

The Financial Accounting Standards Board sets the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) for traditional companies in the U.S., while the International Accounting Standards Board ensures comparability of financial information across international markets. There is no similar standard-setting body that creates principles that apply to all social enterprises. For the sector to achieve the transparency and accountability it needs to attract mainstream capital, more uniform accounting standards should be set—especially for entities that operate under the benefit corporation legal designation. Currently, many impact enterprises willingly enroll in GIIRS impact measurement; however, some form of impact tracking should be mandated through public policy.