Secondary Economic Impacts of a Reduced Bay Area Water Supply

Key Findings

- Large water supply shortfalls during dry years

- Severe dry-year water rationing in the RWS service area

- Building moratoria in affected cities

- Higher Bay Area housing costs

- Increased price of water within the RWS

The State Water Resources Control Board is responsible for setting flow objectives on rivers flowing into the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to protect beneficial uses of water. The Board is considering new regulations aimed at improving fisheries on the San Joaquin River. The regulations, as detailed in the draft Substitute Environmental Document (SED) for the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan update would require an average 40 percent of the river’s natural unimpaired flow to be allowed to flow from La Grange into the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta between February and June, with adaptive implementation ranging between 30 and 50 percent unimpaired flow depending on conditions. Flow objectives would be achieved by curtailing water diversions on the San Joaquin River’s three major tributaries: The Merced, Stanislaus, and Tuolumne Rivers. The Tuolumne River is the primary water supply for the Hetch Hetchy Regional Water System (RWS), which is owned and managed by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC).

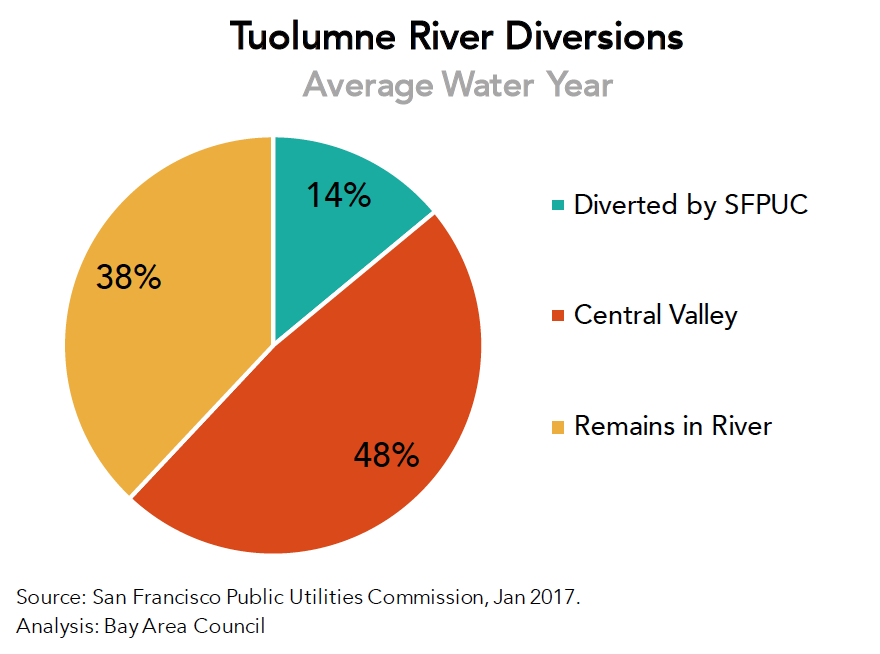

In an average year, about 48 percent of the Tuolumne’s water is diverted for Central Valley agriculture, 38 percent remains in the river, and 14 percent is diverted by the SFPUC. Water from the Tuolumne River is the primary (85%) supply for SFPUC’s RWS that serves 2.6 million people in San Francisco, Silicon Valley, and the East Bay. During dry years, as little as 10 percent of the Tuolumne’s water remains in the river. According to this analysis, meeting the SED’s increased flow requirements in dry years would require major cuts to water supplies for the Bay Area, the Central Valley, or some combination of both.

In an average year, about 48 percent of the Tuolumne’s water is diverted for Central Valley agriculture, 38 percent remains in the river, and 14 percent is diverted by the SFPUC. Water from the Tuolumne River is the primary (85%) supply for SFPUC’s RWS that serves 2.6 million people in San Francisco, Silicon Valley, and the East Bay. During dry years, as little as 10 percent of the Tuolumne’s water remains in the river. According to this analysis, meeting the SED’s increased flow requirements in dry years would require major cuts to water supplies for the Bay Area, the Central Valley, or some combination of both.

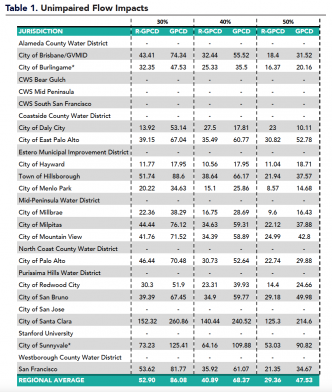

The draft SED does not explain how the cuts would be allocated across users; SFPUC estimates it could be responsible for providing as much as 51 percent of any new flows required. Under that scenario, SFPUC analyzed flow data on the Tuolumne River going back to 1920, and estimated how much water would be available for its Bay Area retail and wholesale customers in each year through 2010 according to five different variables: 20, 30, 40, and 50 percent unimpaired flow, as well as a “base case” without an unimpaired flow standard. SFPUC repeated the analyses under three different demand scenarios: A system-wide demand of 265 million gallons per day (MGD) to represent future conditions; demand of 223 MGD to represent current system demand without rationing and equivalent to deliveries made in FY 2012-2013; and lastly, demand of 175 MGD to represent current system demand including drought rationing equivalent to deliveries made in FY 2015-2016.

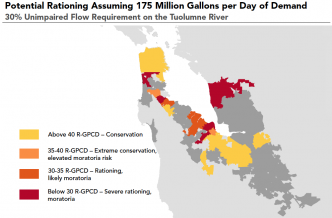

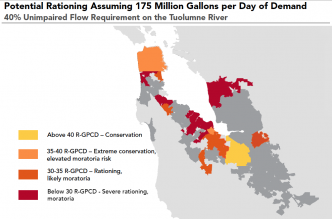

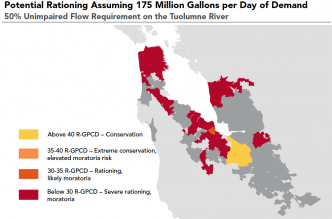

The Bay Area Council Economic Institute looked at the impacts a 30, 40, and 50 percent unimpaired flow requirement on the Tuolumne River would have on Bay Area water users under the 175 MGD scenario. The 175 MGD scenario was chosen because it accurately reflects recent (2015-2016) dry year demand, and therefore represents the worst-case scenario current residents could be expected to face, and city planners would be forced to consider when evaluating available water supplies available for new development.

The key takeaways from this analysis are as follows:

The draft SED could lead to large water supply shortfalls during dry years

According to the SFPUC, RWS supplies would be reduced to as low as 67 MGD from 175 MGD during dry years such as 1990, 1991, 1992, resulting in a maximum annual shortfall of 120,976 acre-feet. The shortfall would have to be addressed either through conservation, the creation of new water supplies, or a combination of both.

The draft SED could result in severe dry-year water rationing in the RWS service area

Using conservation only, RWS users could be forced to reduce water use 55 percent to 30 gallons per residential user per day (R-GPCD) during dry years. Many cities would face R-GPCD requirements that were much lower, such as Menlo Park at just 8.57 gallons. RWS customers currently use 54 R-GPCD, the lowest in California. The California statewide average is 82 R-GPCD.

The draft SED could result in building moratoria in affected cities

Residents in Melbourne Australia, widely regarded as one of, if not the, most water efficient cities in the developed world have achieved 40 R-GPCD. We assume that any Bay Area city which would be forced to plan around dry-year R-GPCD levels below 35 gallons would be compelled to adopt interim controls over new permitting and implement a moratorium on new construction.

The draft SED could result in higher housing costs in the Bay Area

The California Legislative Analyst’s office has found that building less housing than people demand inflates housing prices. Had the draft SED been put in place in 1990, the earliest available housing data provided by the California Department of Finance, we estimate the multiple building moratoria could have resulted in 91,098 fewer housing units over the period ending 2015. Over the same time period, the RWS service area attracted 302,435 new residents. Additionally, SFPUC estimates RWS demand will increase to 265 MGD in the future, meaning the gulf between the Bay Area’s supply and demand will grow over time, further negatively impacting affordability.

The draft SED could undermine Bay Area economic growth

The region served by the RWS supports 3.3 million jobs and generated $667 billion in GDP in 2015. Moratoria on new development will directly undermine the ability of Bay Area employers to grow and create jobs in the region. Indirectly, Bay Area employers increasingly cite the lack of housing as a powerful deterrent to locating new growth within the Bay Area, and report outsourcing new jobs to regions with more affordable housing supplies. By making it harder and more expensive to build, the SED will reinforce this trend.

The draft SED could increase the price of water within the RWS

The above impacts could be avoided, or partially reduced, through securing new water supplies. Due to chronic water supply deficits throughout California, we assume SFPUC will be unable to secure long-term contracts for imported water, and would instead have to create new water either through desalination or water recycling. During dry years at 175 MGD demand, SFPUC estimates the RWS supply will be reduced to 67 MGD, a supply gap of approximately 121,000 acre-feet per year. Producing such quantities of water through desalination would cost an estimated $258 million – $286 million annually, a net cost increase of between approximately $38 million and $66 million to ratepayers. Water recycling wasn’t considered due to the lack of projects at comparable scale.