Pace of Recovery

October 26, 2020

The highlights:

• Between April and September, the Bay Area recovered just over 3370% of the jobs lost between February and April trailing the state and nation. The pace of Bay Area recovery slowed in September. October and November should be better months as reopening is more widespread.

• The regional unemployment rate was 2.7% in February, 13.1% in April and 8.1% in September. Unemployment rates and numbers declined substantially in August, far more than is consistent with the modest job growth.

• This update also looks at industry sector trends, air travel data, 2019 ACS data and the Bay Area Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA)

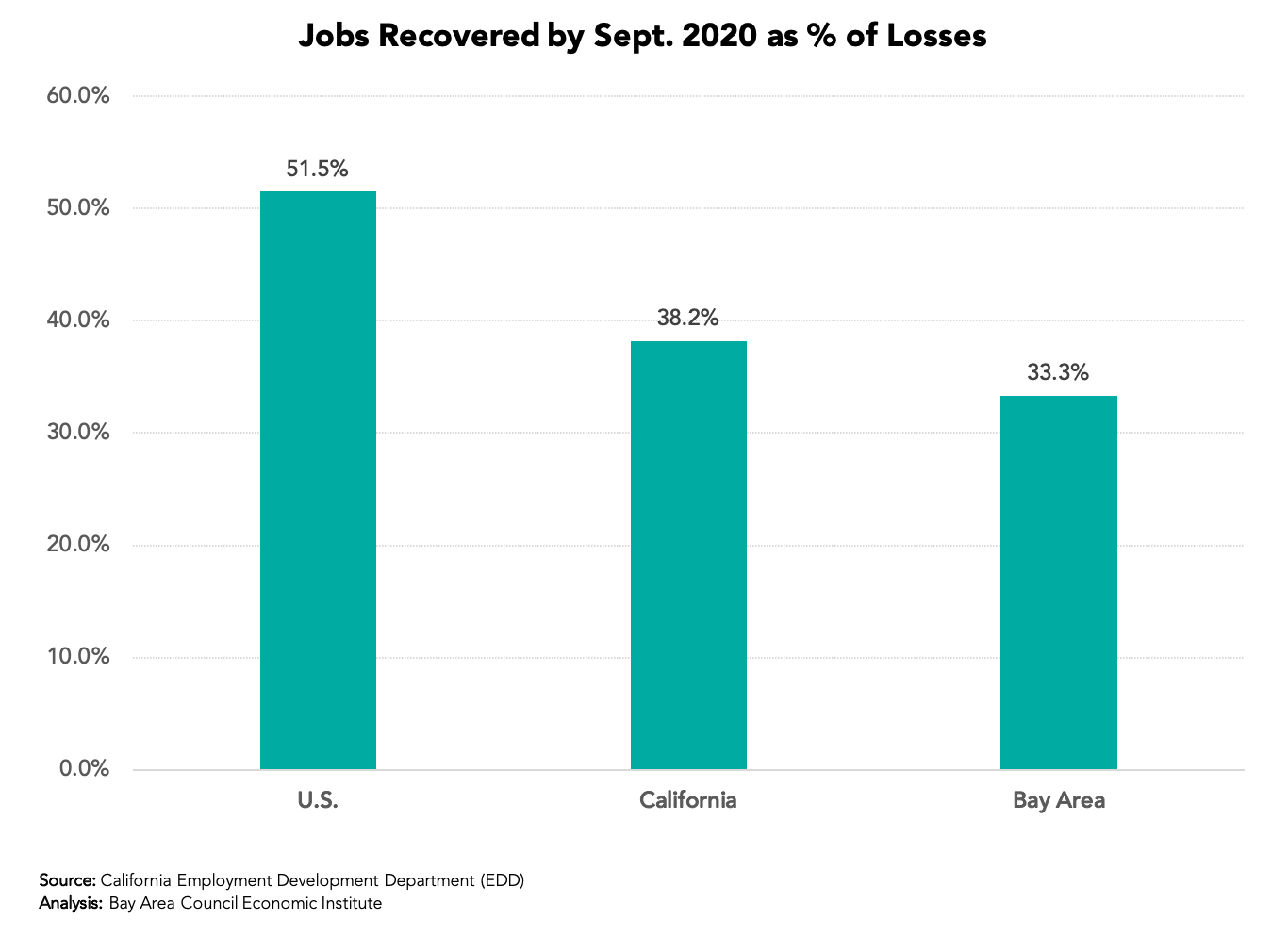

California and the Bay Area Lagged the Nation in Job Recovery in September

The state and Bay Area recovered a smaller share of the jobs lost by September compared to the nation. This is the result of our more cautious reopening pace and the more than 80% decline in business and visitor travel and resulting loss of spending and jobs. The Bay Area is now reopening more businesses (Santa Clara, Napa and Alameda counties are now in the orange tier this month and SF has achieved the yellow tier) but the impact will not be seen until the November jobs report.

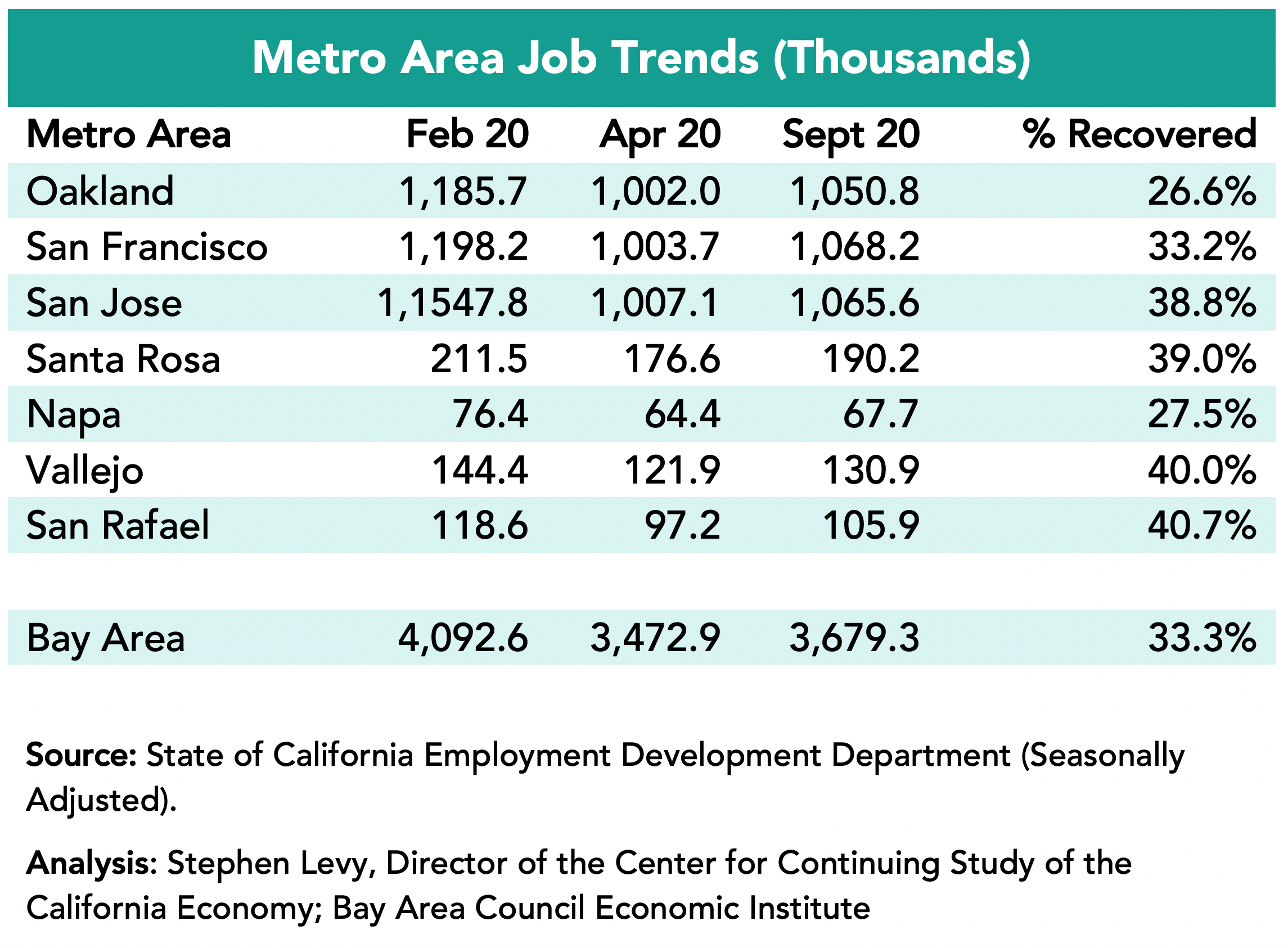

The Bay Area added 18,900 jobs in September down from 30,600 in August.

The share of jobs recovered by September varies somewhat among the metro areas with the largest share recovered in the San Rafael metro area (40.7%) and the smallest share in the Oakland metro area (26.6). The San Jose, Santa Rosa and Vallejo metro areas beat the regional recovery average.

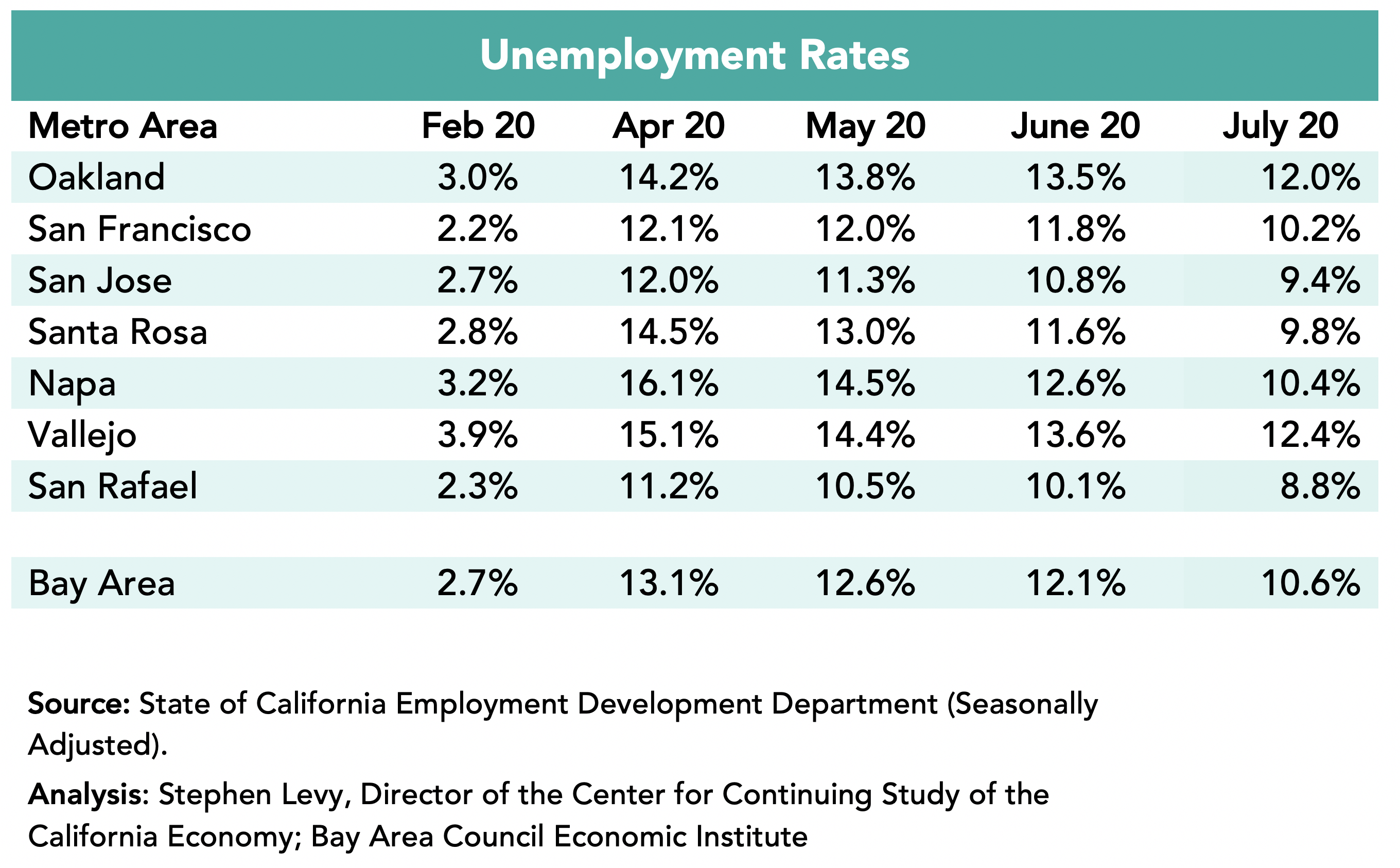

Unemployment rates rose sharply between February and April throughout the region. September data showed small declines in unemployment rates across the region. The regional unemployment rate declined from 13.1% in April to 8.1% in September. All metro areas had rates below 10%. However, part of the drop may be the result of unemployed workers leaving the labor force.

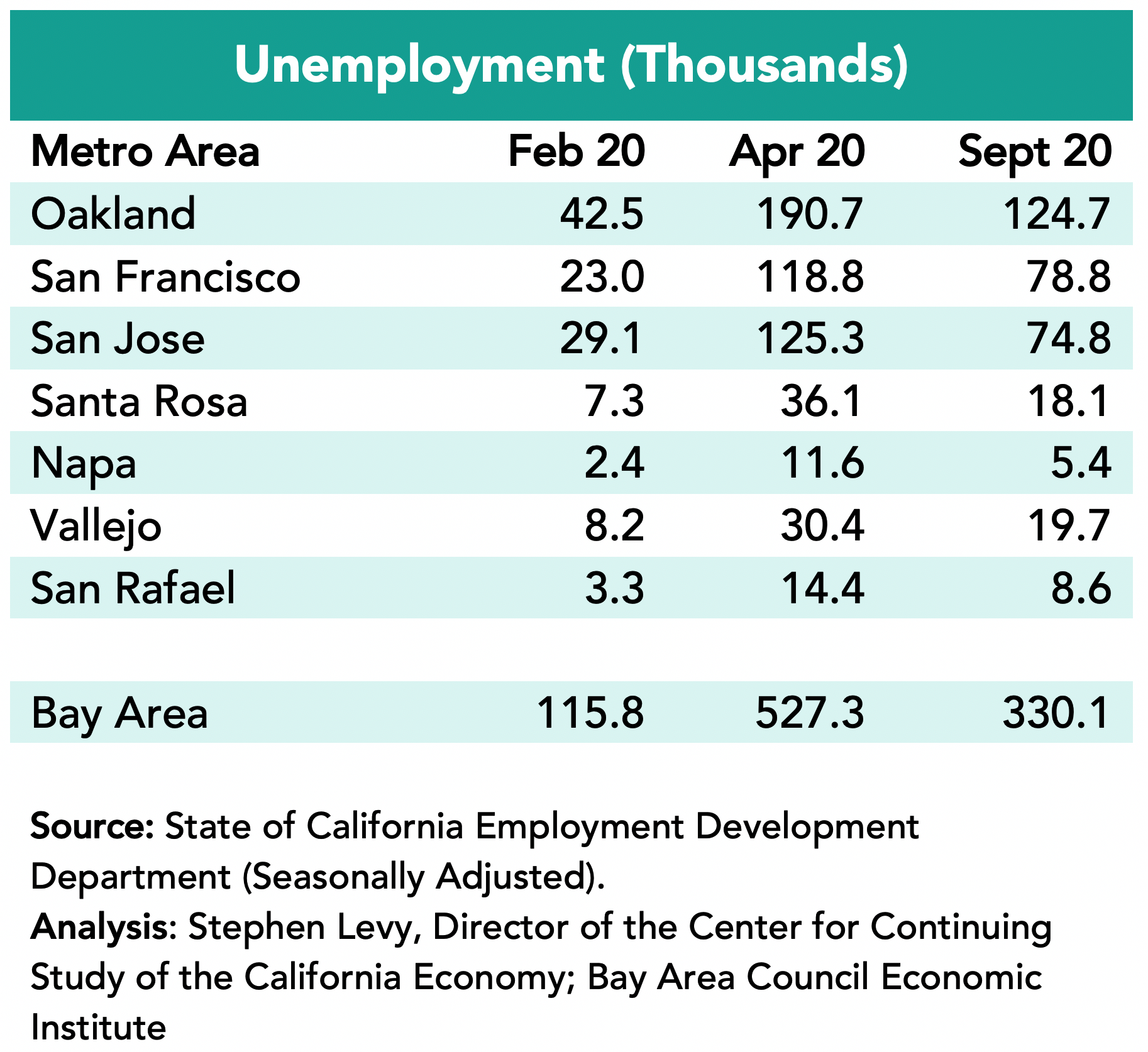

The number of unemployed residents fell quite a bit in September to 330,100 from 527,300 in April. This estimate is hard to explain given the much smaller reported job gains and the decline of more than 50,000 in the number of workers in the labor force in August.

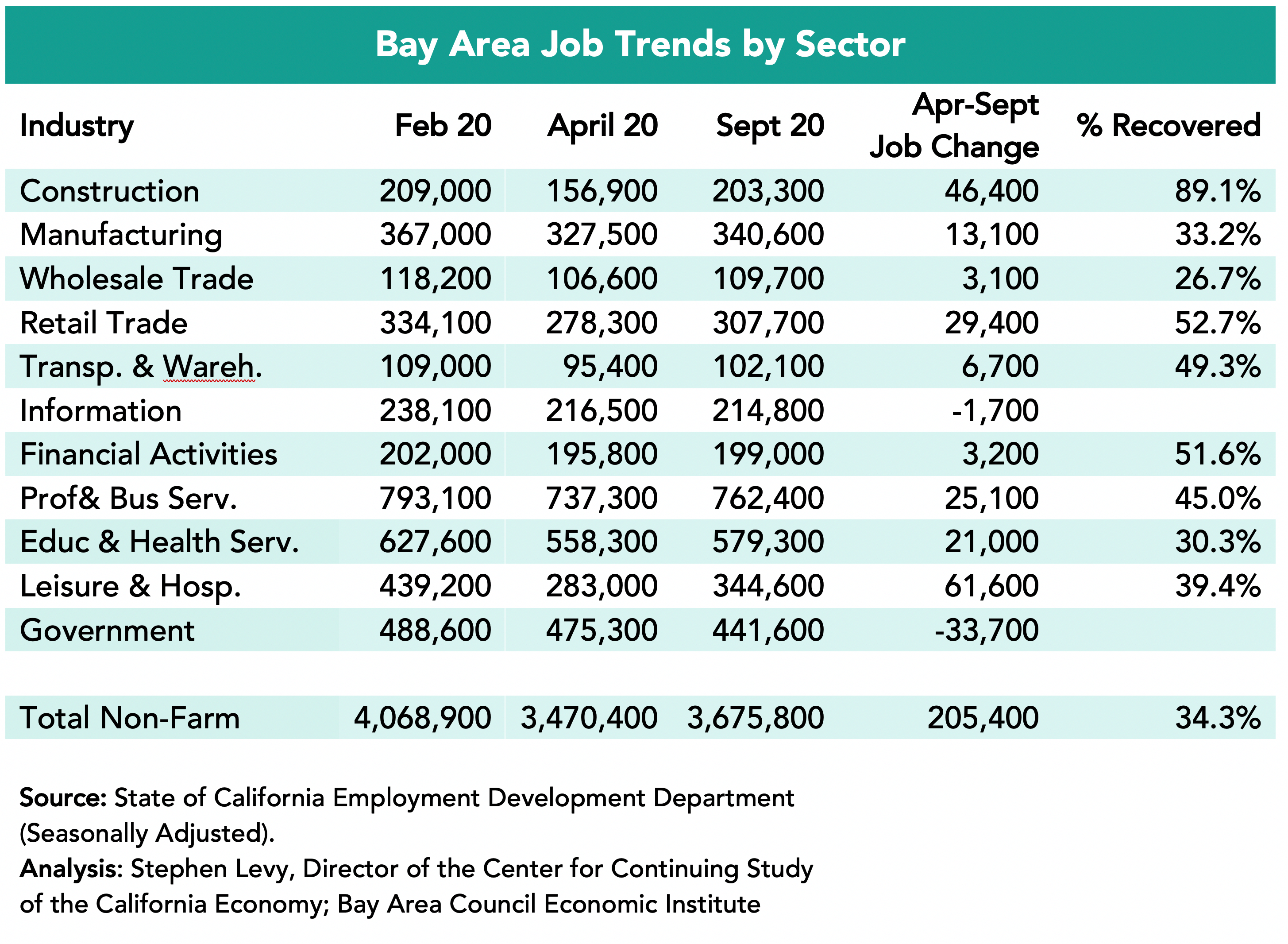

The largest job losses were in Leisure and Hospitality where half the jobs went away between February and April. Construction showed the biggest recovery by September (89.1%) while the Wholesale Trade sector had a relatively small recovery rate so far. Government is the only sector to lose jobs after April. The overall job losses and recovery are affected by the continuing decline in Information and Government jobs. November should bring stronger recovery as some counties are now allowed to broaden the reopening process.

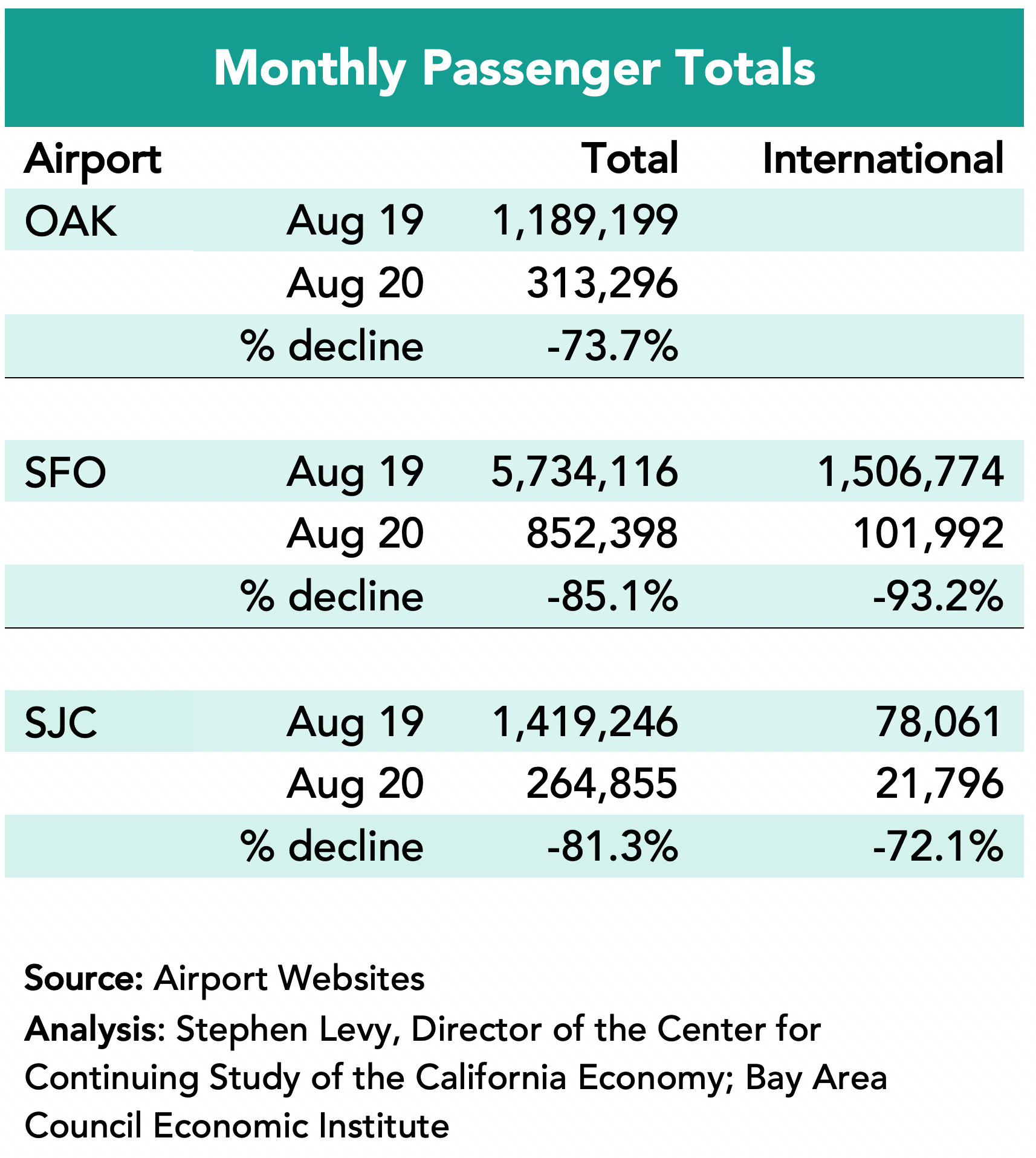

Air travel plummeted after February with losses of 90% or more. There was a small rebound in August but air travel remains deeply depressed.

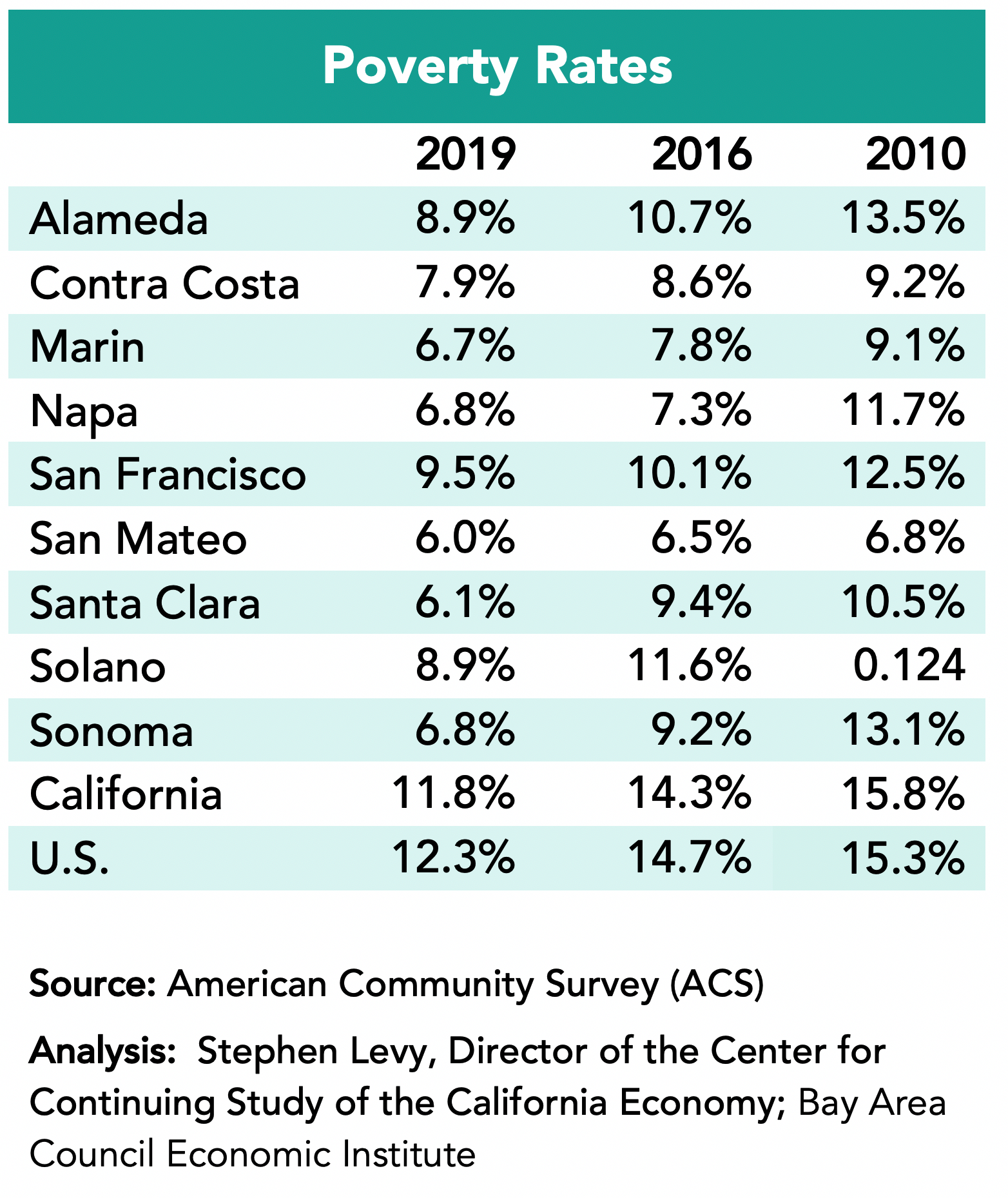

Bay Area poverty rates declined in 2019 and median household income increased as reported last week in the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) data release.

Bay Area poverty rates (not adjusted for housing costs were all below 10% in 2019, below the state and national rates and well below poverty rates in 2010 and 2016. The Census Bureau publishes a supplemental poverty rate for states adjusted mainly for housing costs. In 2019 California’s supplemental poverty rate was 17.2% compared to the official rate of 11.8%

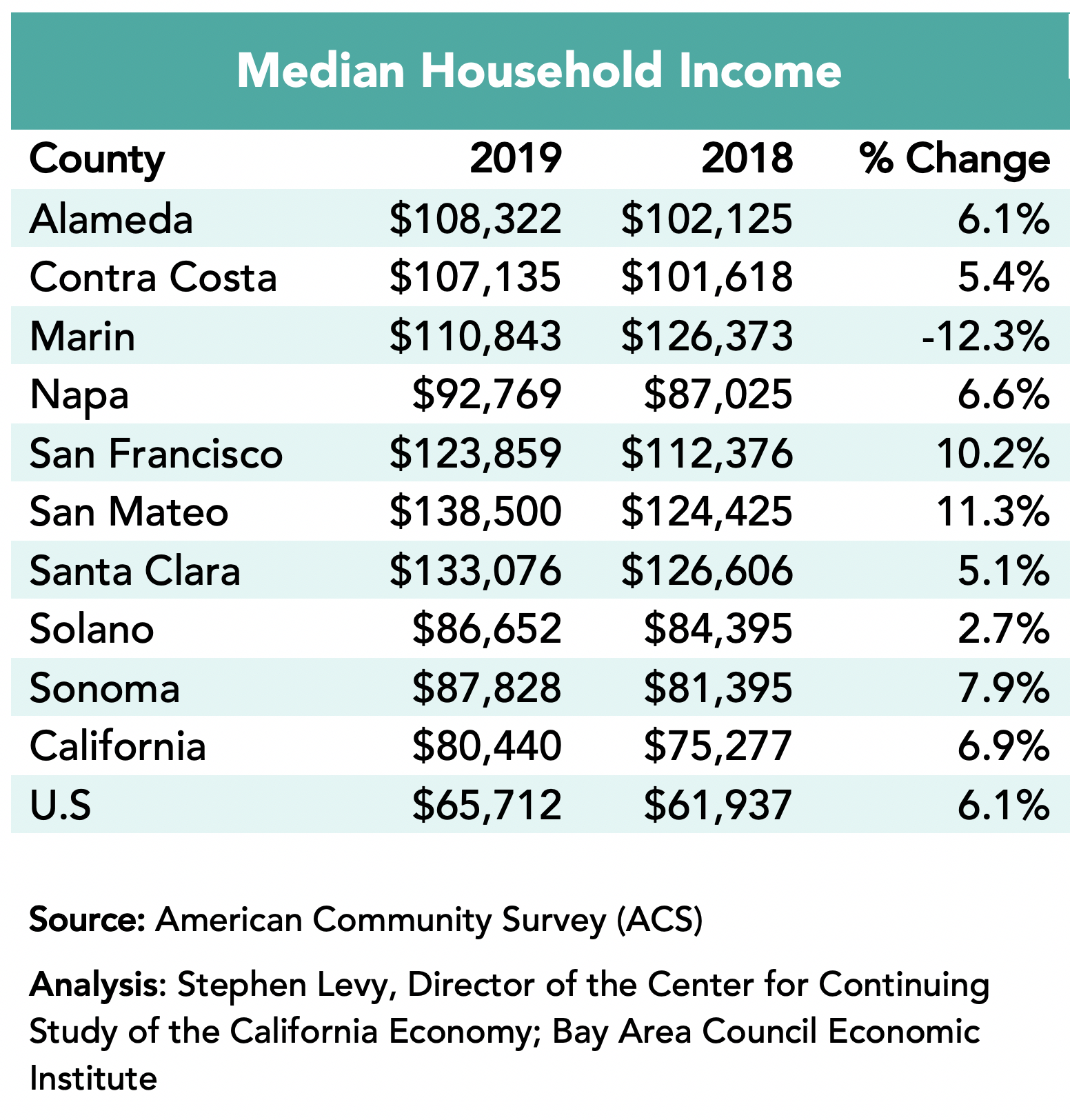

Median household income increased in most Bay Area counties in 2019. I checked the Marin County result and that is what the website shows though it seems odd. These gains adjusted for inflation far outpaced the Bay Area increase in consumer prices.

The ABAG RHNA allocation methodology committee made their final recommendation on Friday. The regional allocation from HCD is described first and then the decision on local area allocation afterwards.

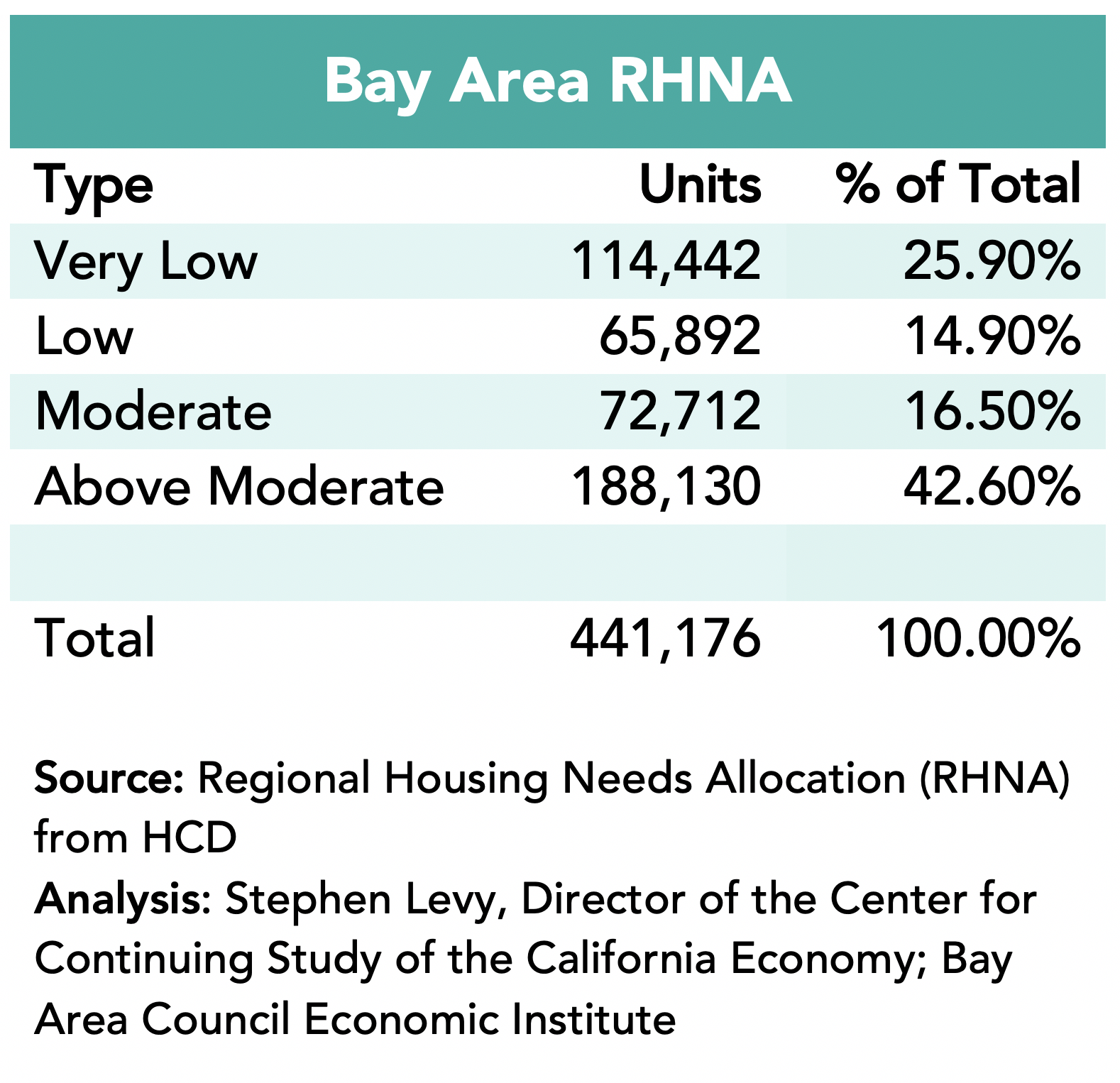

The California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) just released the Regional Housing Needs Determination (RHNA) for the Bay Area for the period from June 2022 through December 2030. The HCD letter can be seen at https://hcd.ca.gov/community-development/housing-element/docs/ABAGRHNA-Final060920(r).pdf. The Bay Area target is 135% higher than the current target and includes 441,176 units distributed among four income groups – very low (for residents up to 50% of area median income (AMI)), low (50% to 80% of AMI), moderate (80% to 120% of AMI) and above moderate. A majority of the units needed are in the very low to moderate income groups.

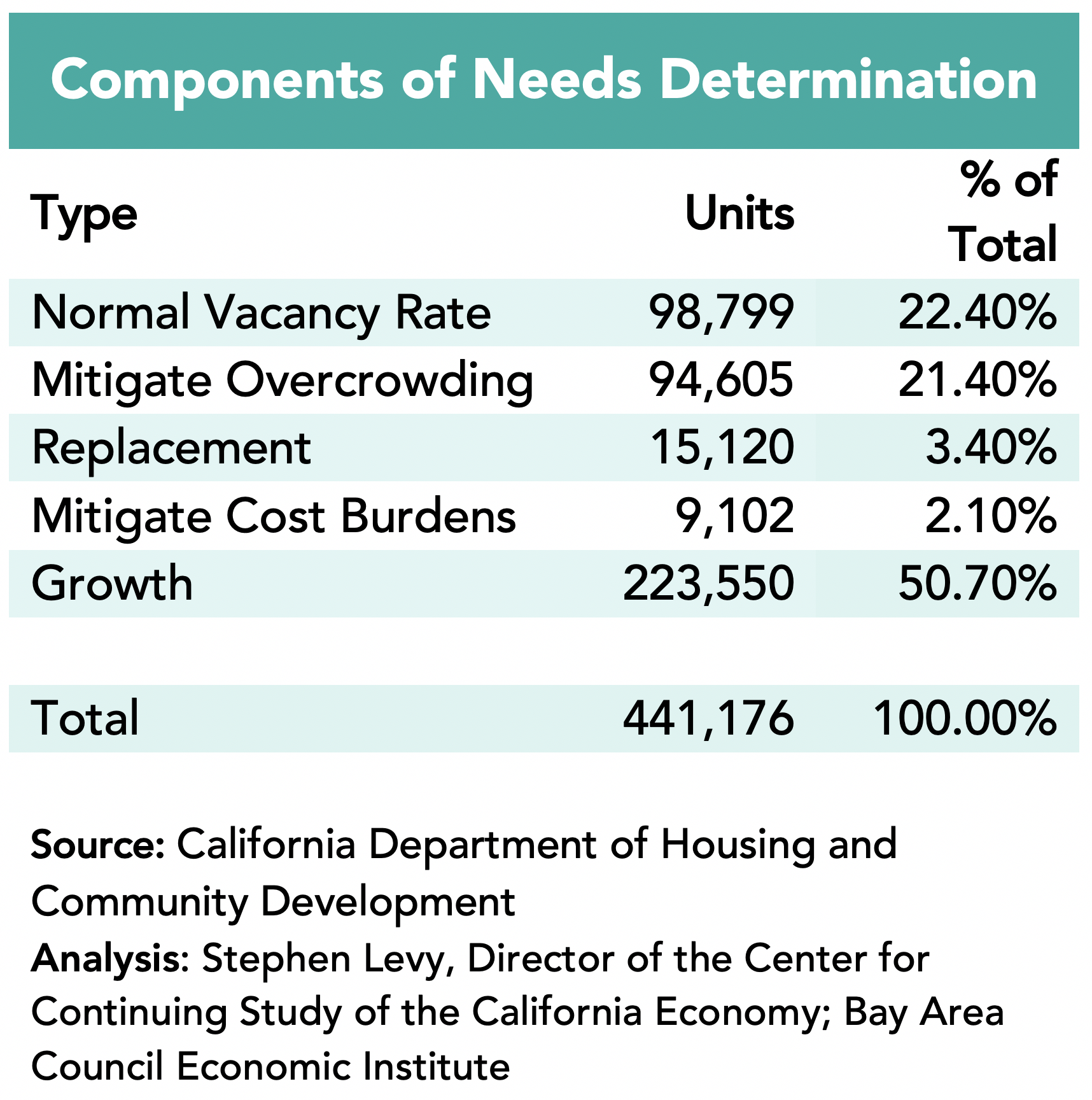

HCD used a new methodology to develop the needs assessment. Recent state legislation required HCD to include housing units to reduce the number of households that are overcrowded and cost-burdened. HCD compared the Bay Area to shares in comparable regions. HCD has always included units to return the region to a normal vacancy rate and to replace demolished housing.

The final determinant is allowance for units to accommodate the region’s expected growth. HCD used new population projections from the state Department of Finance (DOF) instead of the regional growth forecast developed by ABAG that projected 400,000 more residents than DOF in 2030.

Only half of the Bay Area housing needs according to this analysis come from growth. The rest come as a result of correcting existing shortages.

The next step is for ABAG to allocate the units to local areas, which will take place over the coming months. Current emphasis is on allocating units more to areas that have high amenities and to areas that have substantially more jobs than housing.

The ABAG RHNA allocation methodology committee recommended an approach that allocates an above average share of the regional RHNA to cities that are considered high opportunity areas and cities that have good auto and transit proximity to jobs. The result is that the largest % increases in housing went to communities along the peninsula.

The details and city by city allocations are found in the meeting materials that can be found on the ABAG website.

The recommended allocation is alternative 8A that allocates 70% of the low and very low-income units based on high opportunity areas and 15% each to proximity to jobs for transit and autos. For moderate and above moderate income units the allocation was based 40% on high opportunity areas and 60% on auto proximity to jobs.