by Tracey Grose & Patrick Kallerman

Last Tuesday, a U.S. District judge in San Francisco granted class-action status to a lawsuit brought by three California Uber drivers. The case could ultimately decide one of the biggest unanswered questions of the so-called “1099 economy”: do we have an independent contractor problem? Are all participants (in this case, Uber drivers), independent contractors, or do some qualify as actual employees? Are 1099 jobs inherently subpar, or do some models offer new flexibility to the benefit of both worker and employer?

The new technology platforms that bring greater flexibility to the marketplace by enabling short-term and task-based work are diverse, as are the business and earnings models underlying them. During an era of wage stagnation and growing income disparity, and with increasing numbers of businesses and services relying on independent contractors, how the courts decide on this matter could have immense consequences for work and business models in the future. At the same time, we know surprisingly little about this segment of the economy: how big it is, or how fast it’s growing. Better understanding the changing nature of work is essential to informing any policy action targeting an increasingly diverse field of new work models.

The 1099 Economy: Hot or Not?

The recent growth of the segment of the labor force made up of contract workers — sometimes known as freelancers, gig-workers, supertemps, or 1099 workers (“1099” refers to the IRS Form 1099-MISC used by independent contractors) — was initially described as a tidal wave. Reports speculated on a massive rise of individuals choosing contract work over traditional arrangements, an increasing reliance on this work by businesses of all sizes, and how the dependence on contract work will reshape the economy and careers.

A second wave of commentary asked whether this trend was of any consequence at all. Recent reports have questioned the sustainability of the gig economy, raised concerns about the implications for individuals of on-demand work, and even suggested that individuals are less likely than ever to be self-employed or to hold multiple jobs.

However, both narratives are oversimplifications inconsistent with close analysis of the data.

The Contingent Workforce Goes Underground

Originally known as “contingent workers” — a term coined in 1985 by labor economist Audrey Freedman — part-time, on-call, and self-employed individuals have consistently represented a sizable portion of the labor force. Census estimates from the 1990s and early 2000s put its share at a steady one-third of workers.

When the source of these data — the Contingent Work Supplement — was discontinued in 2005, statistics on this workforce became surprisingly difficult to find. So much so that Senator Mark Warner — who is emerging as the leading champion of policy reform in this area — has requested that the Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the IRS produce additional data to help inform the debate.

In the absence of more detailed data, many have pointed to the sharp rise in the Census Bureau’s Nonemployer Statistics as evidence of the growing 1099 economy. Defined as individual proprietorships, partnerships, or corporations with no employees, the number of nonemployer firms has increased by nearly 18 percent since 2004, compared to a 3.5 percent increase in payroll employment. Patterns vary by industry sector with Utilities, Transportation and Warehousing, and Real Estate topping growth in nonemployer firms last year. This story becomes even more interesting when broken down by occupation.

While the Nonemployer Statistics may be a reasonable measure, they do exclude certain individuals and aspects of the 1099 economy. For example, firms and individuals only show up in the Nonemployer Statistics once they have earned over $1,000 in a year on the theory that these activities are more likely to be hobbies rather than businesses. These data also lack insight into the volume of gigs being performed. A more reliable way to gauge the size of this segment of the labor force and the number of gigs worked is through Internal Revenue Service data.

An Explosion in 1099s?

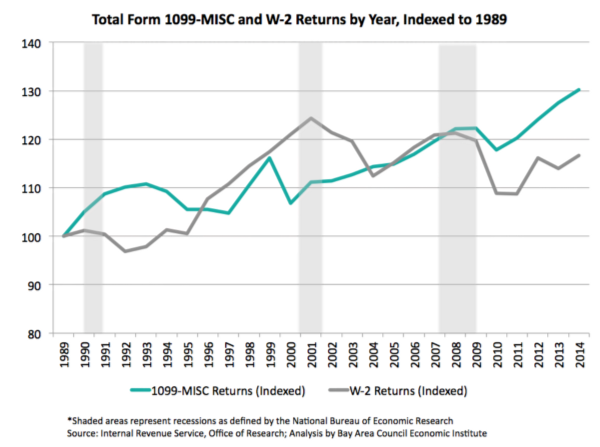

The chart below uses previously unanalyzed data obtained from the IRS’s Office of Research and reflects the growth in 1099s vs. W-2s, indexed to their levels in 1989. Interestingly, we see that growth in the number of issued 1099s had previously been very strong primarily following the recessions of 1990, 2001, and 2007. However, since the end of the latest recession in 2009, the growth has steadily continued, whereas the rise in W-2s has come in fits and starts.

So why are so many more 1099s being issued? While it is true that any single individual can receive multiple 1099s, the rising number of 1099s means either the same number of individuals is taking on more “gigs,” more individuals are joining the 1099 economy, or both. Again, the story is mixed. Coming out of the last downturn, the San Francisco Federal Reserve points out that involuntary part-time employment has remained stubbornly high, and individuals aren’t finding as much work as they need. Platforms like Lyft, Uber, TaskRabbit, and Instacart have made participating in the 1099 economy much easier, a trend that has also shown up in the Nonemployer Statistics. The new flexibility that these platforms offer also enables new earning models for people with limited availability or who are between pursuits.

Technology continues to be a formidable driver of economic change, and the tools we have for tracking change will always lag behind. There is more to learn, and what we learn about the nature of the contingent economy and the changing nature of work generally must drive our policy responses. Precipitous legal and regulatory responses risk squelching innovation and growth without the knowledge of whether these interventions will have positive outcomes.