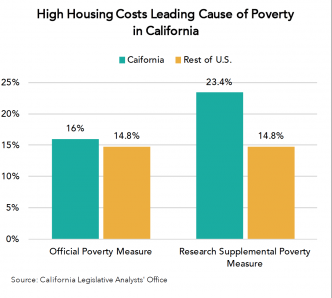

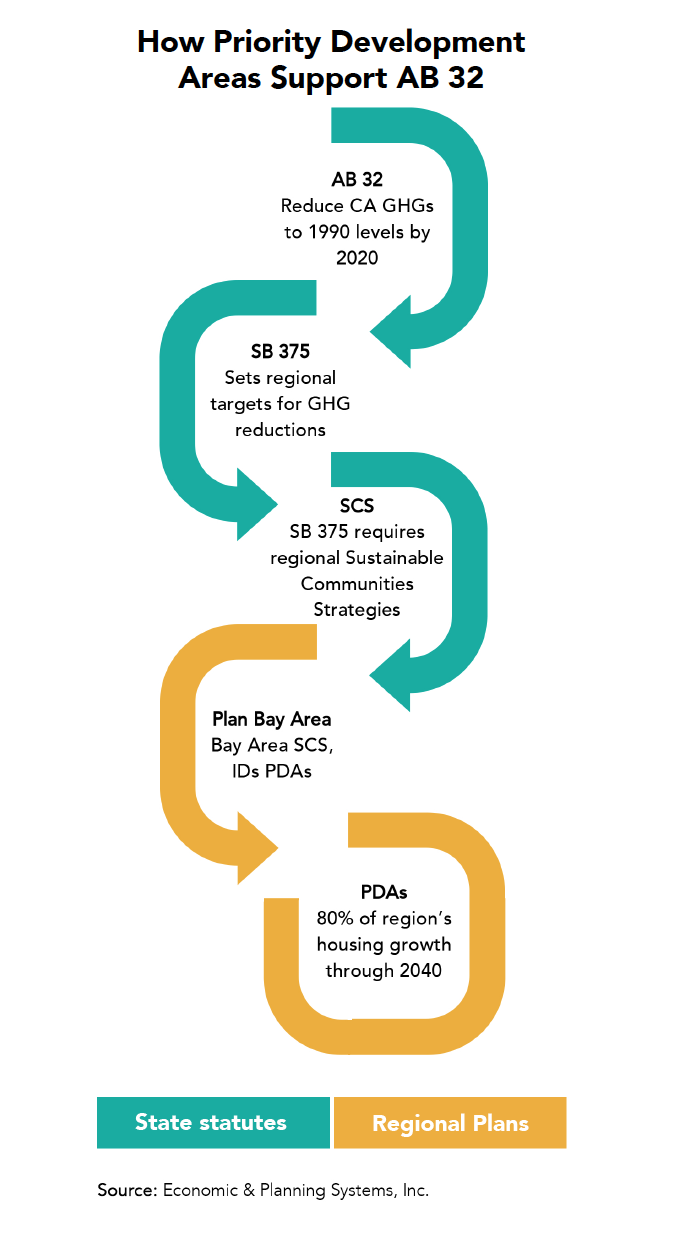

In order to meet the ambitious goals set by AB 32, the Bay Area must take a different approach to housing its growing population. By aggressively increasing the production of housing and focusing on Priority Development Areas, the region can reach its emission targets, strengthen its economy, and increase affordability and equity.

The strategies below should be considered with the overall goal of building—not simply planning, or zoning, or even permitting—sufficient housing stock, particularly in Priority Development Areas, to meet the demands of a growing regional population and fill historic deficits.

Strategy #1 – Streamline approvals for new housing developments that meet local planning and zoning requirements. Discretionary reviews and other appeals far too often delay or completely block developments that meet local planning and zoning requirements. Abuse of the California Environmental Quality Act is a prime example. Right-to-build legislation—like the Governor’s proposed “Streamline Affordable Housing” bill—is essential to making real progress in building new housing, particularly within Priority Development Areas.

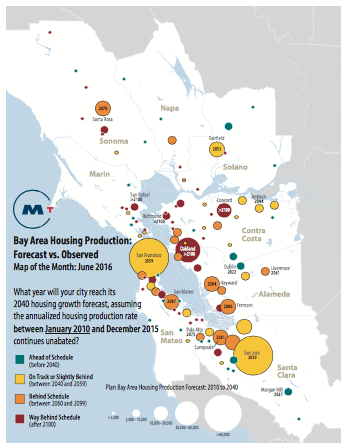

Strategy #2 – Cities must be held accountable for meeting Regional Housing Needs Allocations (RHNAs) and Priority Development Area (PDA) growth. Cities that meet their RHNA obligations should be rewarded, and there should be real consequences for failing to permit the required number of new housing units. Further incentives should be awarded to cities that streamline the approval process for new housing and bring units to market faster and at lower cost.

Strategy #3 – The Bay Area must expand the stock of secondary units, junior units, “in-law” units, and other similar uses of homes and lots as an additional affordable housing resource. This is a quick and inexpensive way to add housing in a very short amount of time. These additions to California’s housing supply have low carbon footprints, are affordable by design, and can be placed into existing neighborhoods.

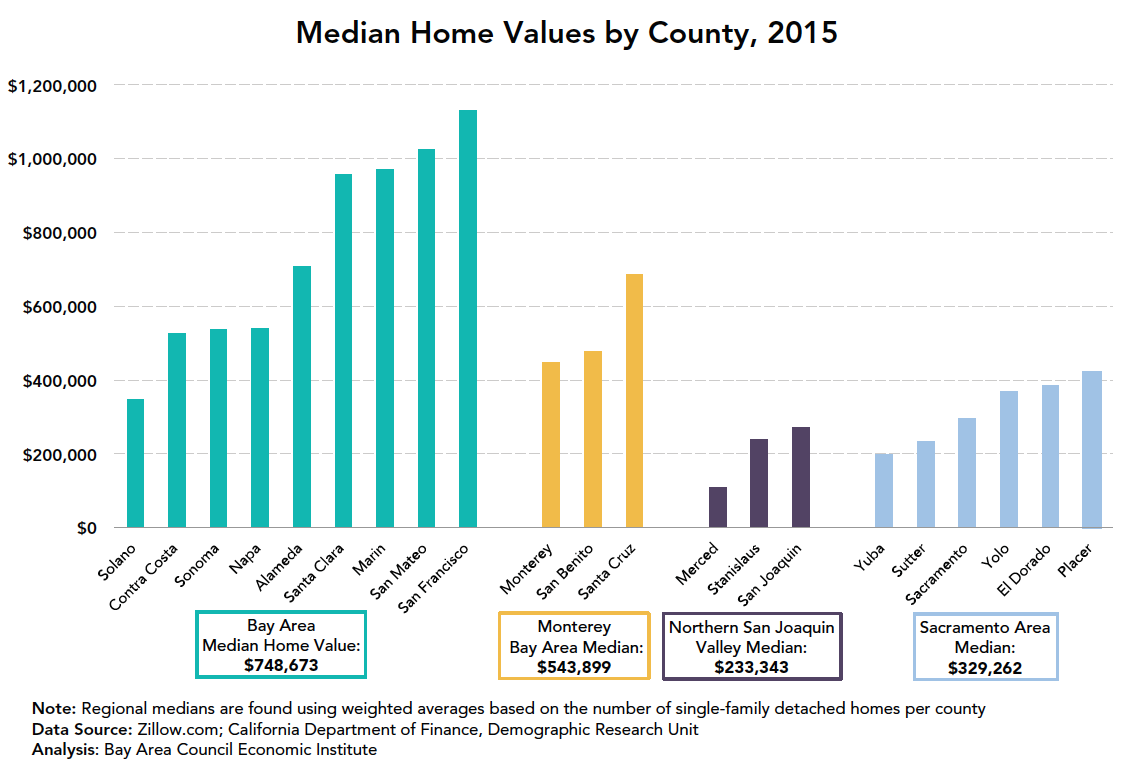

Strategy #4 – The update to Plan Bay Area must have a strong foundation in the economic realities of development. In the first iteration of Plan Bay Area, there are too many instances in which development densities were recommended for locations where they were not viable given market conditions; local market rents are not high enough to support the proposed construction types in many areas.

Strategy #5 – The fiscalization of municipal land use decisions needs to change. When Proposition 13 passed in 1978, revenues to local governments were cut by about 57 percent. This forced towns and cities across California to look for new sources of funding for essential services and to avoid land uses that generate more demand for services than tax dollars. In the creation of their general plans, local governments turned to job-generating uses, hotels, and retail as preferable fiscal alternatives to housing. Local jurisdictions keep a much greater percentage of sales taxes and transient occupancy taxes than property taxes and, as a result, they now zone far too much land for hotels, stores, and auto dealerships. The demands for services such as libraries, schools, and other essentials are proportional to the housing in local jurisdictions, so even office uses are seen as preferable to housing because workers who go home at the end of the day to a different jurisdiction do not generate those demands for services locally. The notion that housing does not pay for itself may reflect reality in some instances, but as prices have risen in many areas of the region, housing increasingly generates sufficient taxes to support a broad array of services for cities.

Strategy #6 – Policymakers need to reconsider discretionary costs added to the fixed costs of construction, especially if the construction of more housing—and particularly more affordable housing—is a priority. The cost of constructing a new home is driven by many factors: supply and demand, materials costs, labor costs, land acquisition costs, financing costs, parking mandates, municipal fees, lawsuits, and time. Some of these costs are inflexible, and there is little that can be done to change them via public policy. But other costs are driven by policy choices. Policymakers need to review some of these choices and make changes.

Strategy #7 – Establish powers to acquire funding and assemble the necessary land for development in urban areas and in Priority Development Areas. With the loss of over 400 Redevelopment Agencies (RDAs) across California in 2012, it was estimated that California’s affordable housing developers lost $1 billion annually in funding to build much needed housing. Thirty-five of those RDAs also had the power to create one developable plot of land by assembling the sorts of small and oddly shaped parcels that are common in urban areas. Absent that power, it becomes more difficult for developers to acquire land to develop in urban areas and in Priority Development Areas.

Strategy #8 – Require the Legislative Analyst’s Office to conduct an analysis on any legislation proposing an increase to the cost of new housing construction. California’s housing shortage is well documented, as are its consequences. In order to ensure that the shortage does not get worse, an analysis should be conducted of any new legislation that might increase the cost of construction or have other unintended consequences.

Strategy #9 – Extend the state’s cap-and-trade program through 2050. California’s cap-and-trade program is essential for achieving its 2030, 2040, and 2050 climate goals. The program also provides essential funding for low carbon transportation, transit-oriented development, and affordable housing.

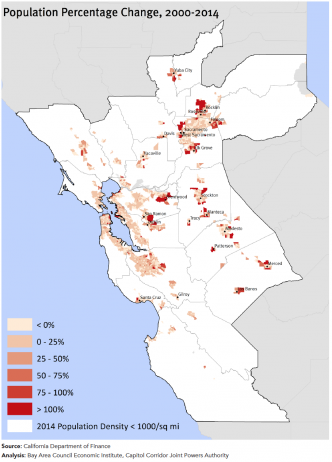

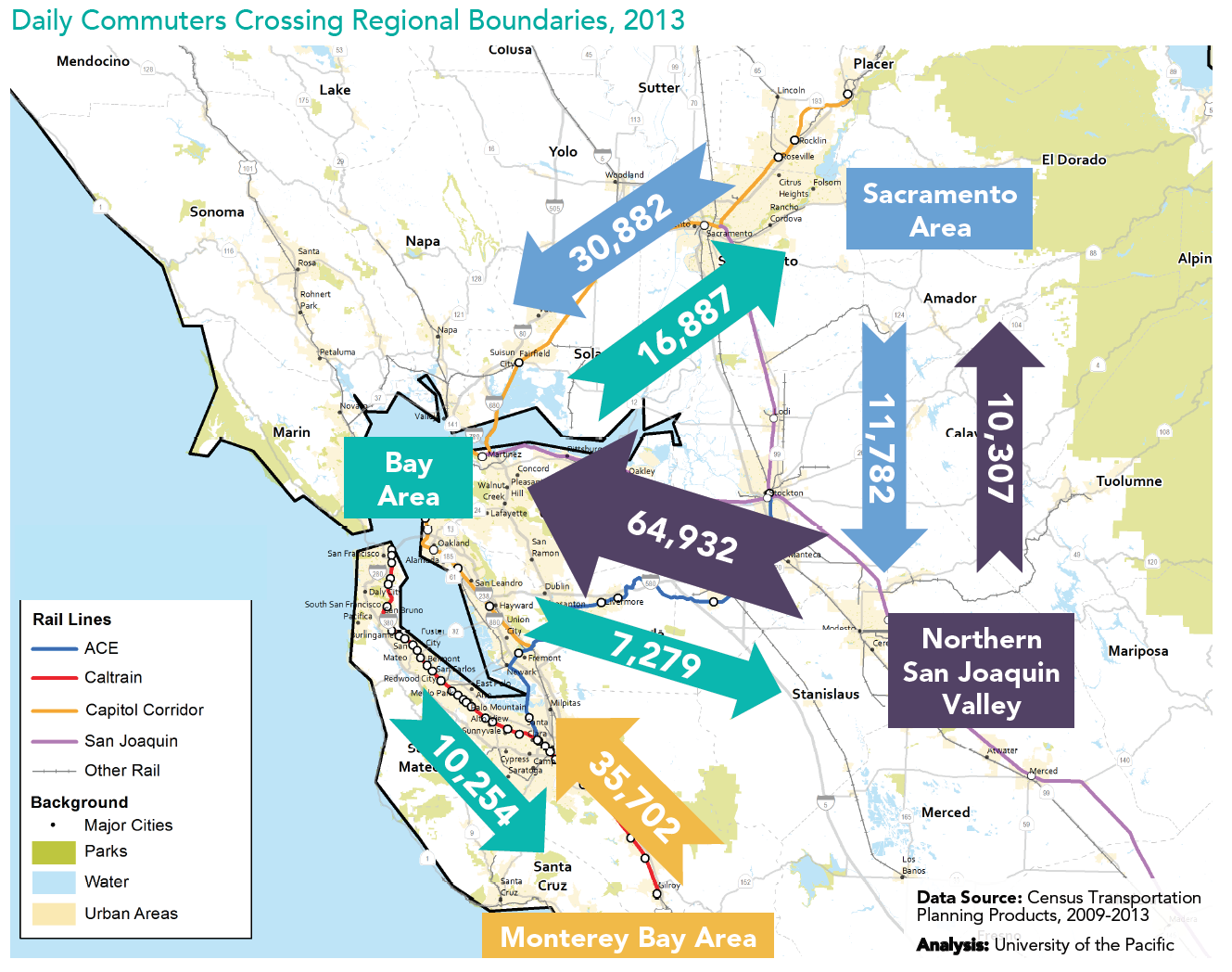

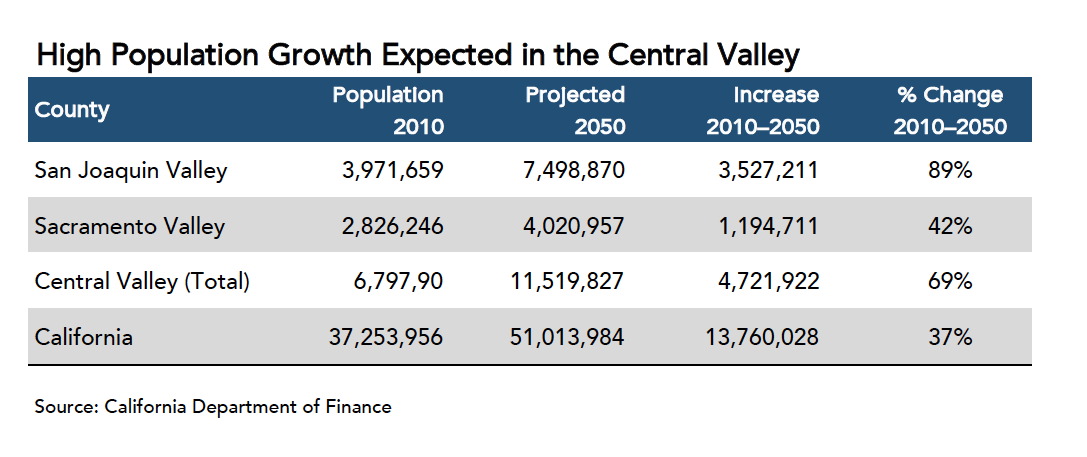

Strategy #10 – Begin to seriously plan for the megaregion. Despite state planning goals, the growing megaregion has become the most rapidly accelerating new development pattern unfolding in California, and it can no longer be ignored. California’s planning goals, including building sustainable communities, will not be achieved without major additional changes to infill development control policies. Land use policies must change in a profound manner to allow more infill to occur more affordably, and state planning efforts must expand their scale to more effectively address megaregional growth.

Read the Full PDF Report on Another Inconvenient Truth »