Predicting an impending end to this historic run has become a cottage industry, and certainly the Bay Area’s ongoing economic success cannot be taken for granted. For all of its advantages, the Bay Area is not inoculated against the impacts of national and international business cycles. In fact, the region has historically had higher peaks and lower valleys in its economic cycles when compared to the rest of the nation. Most notably, the regional economy had to reinvent itself after the dot-com crash of the early aughts. The largest current threats to ongoing prosperity in the region emanate from Washington, DC, where a series of policy choices is undermining the international economic cooperation and exchange of people and ideas that help to power the Bay Area’s economy. These concerns are real, but the doomsayers focus too often on the dark clouds on the horizon, rather than on the green shoots coming out of the ground all around them.

A perfect encapsulation of this dynamic occurred when Charles Schwab, the legendary founder of the San Francisco-grown brokerage, warned in mid-May 2018 that people and companies were fleeing the state due to the federal legislation eliminating the deduction for state and local taxes. This was a policy choice that will have a large impact on high-income earners in the Bay Area, and the company Schwab founded is an example of one that has recently moved many jobs to other states. Just two weeks earlier, however, the Charles Schwab Corporation announced that it had chosen San Francisco as one of its two sites for new digital accelerators linked to hundreds of high-wage jobs and a significant new real estate footprint. And although the federal tax reform package will have an unquestionable impact on the region’s high earners, it is also providing a tremendous windfall to Bay-Area-based companies. These companies are using the savings to make massive personnel and real estate investments in the region. Not the least of these are the planning of a transit-oriented campus in San Jose by Google, the leasing of an entire 43-story office tower in San Francisco by Facebook, and the creation of a spectacular new “spaceship” campus in Cupertino by Apple. And such growth is fanning out across the region, with cranes filling the skies in Oakland as it experiences its biggest surge in residential and commercial development since the 1990s.

The myth that high earners and high-productivity companies are fleeing the region has had it exactly backwards for long enough that more people ought to have noticed. In fact, during a period when the Bay Area’s economic growth has outstripped that of all of its domestic competitors, the Bay Area—and the state of California generally—have been net importers of higher-income individuals. The challenges have come for lower-margin industries as well as the lower-wage workers who are either leaving the state or traveling increasing distances as mega-commuters from the broader Northern California Megaregion that includes the Sacramento and Monterey areas and the San Joaquin Valley.

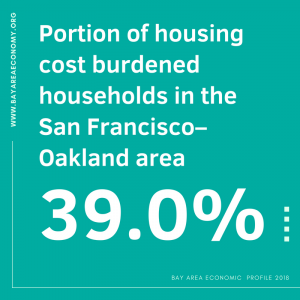

But in spite of being home to the spectacular economic engine of the Bay Area, the state of California also has the highest levels of real poverty and child poverty in the nation. Many of the Bay Area’s residents are housing cost burdened, and homelessness has increased. What is often missed, however, is that housing costs and homelessness are rising across a broad range of geographies in the United States, not all of which are nearly as economically successful as the Bay Area. What makes the Bay Area different, therefore, is not its challenges, but the resources and innovative minds that it can bring to bear to address them.

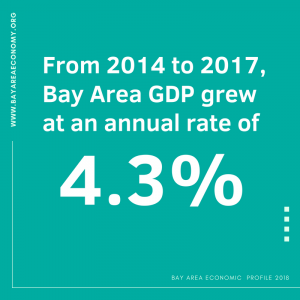

As private- and public-sector leaders make economic and policy decisions, they must be informed by the best possible objective analyses and eschew the many myths that attach themselves to culturally significant and economically successful geographies such as the Bay Area. This report endeavors to provide just such data and analysis. Its first chapter lays out the top-level economic data on the robust and highly-productive regional economy. The second chapter drills down into the specific assets of and advantages provided by the San Francisco-Silicon Valley Bay Area’s innovation economy. The third chapter details some of the challenges facing our regional economy in areas from housing to transportation to human well-being. And the final chapter expands the focus to the Northern California Megaregion, the area that is increasingly the relevant economic unit for both domestic commute sheds and goods movement, as well as international economic competition.