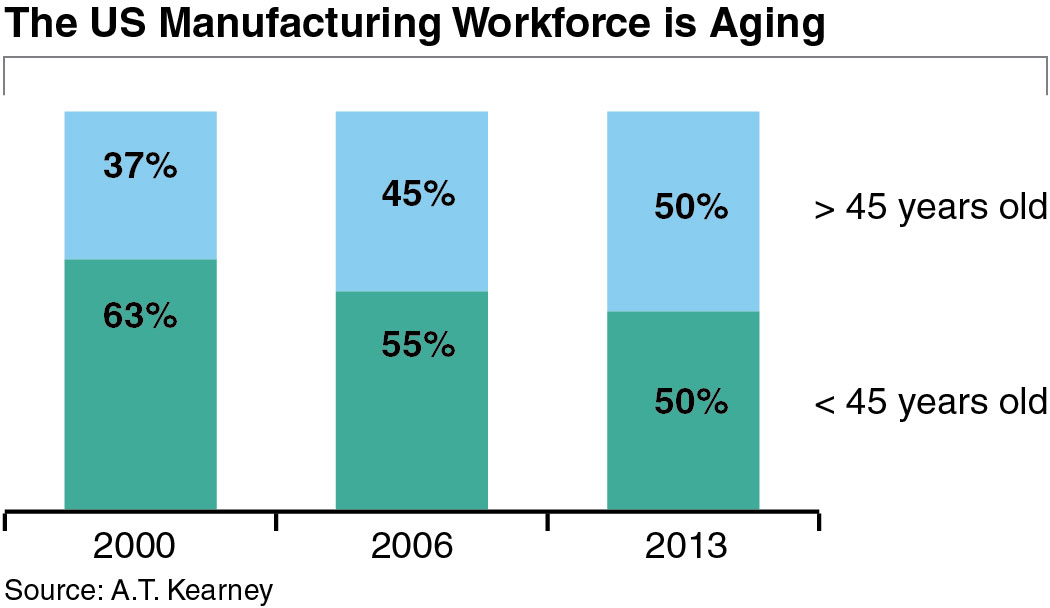

Advanced manufacturing requires advanced workforce skills. As the existing manufacturing workforce ages and nears retirement, recruitment poses a major challenge for producers of advanced products or those utilizing advanced processes. Initiatives are needed to match workforce training with the needs of manufacturing employers, through apprenticeship and career technical education programs and a statewide certification system geared to advanced manufacturing skills.

In a 2011 Deloitte survey of manufacturers, 74 percent of respondents indicated that workforce shortages or skill deficiencies in production roles were having an impact on their ability to expand operations or improve productivity. In some cases, the loss of manufacturing activities has eroded the technical skills base, pushing manufacturers to locate in other locales.

What Exists Today

Of the $4.3 billion spent annually by the federal government on technology-oriented education and training, only one-fifth goes toward programs supporting vocational and community college training programs. Given this level of national funding, California workforce programs for manufacturing have been centered on better utilization of the community college system to place students on career paths in manufacturing.

Under the California Community Colleges Economic and Workforce Development Program, industry-specific workforce services are coordinated by regional Deputy Sector Navigators who align community college and other workforce development resources with the needs of industry sectors. Advanced manufacturing is one of 10 priority areas under the program, with goals that include identifying and filling gaps in community college curricula with the help of industry partners and attracting more students to career paths in manufacturing and other technical areas.

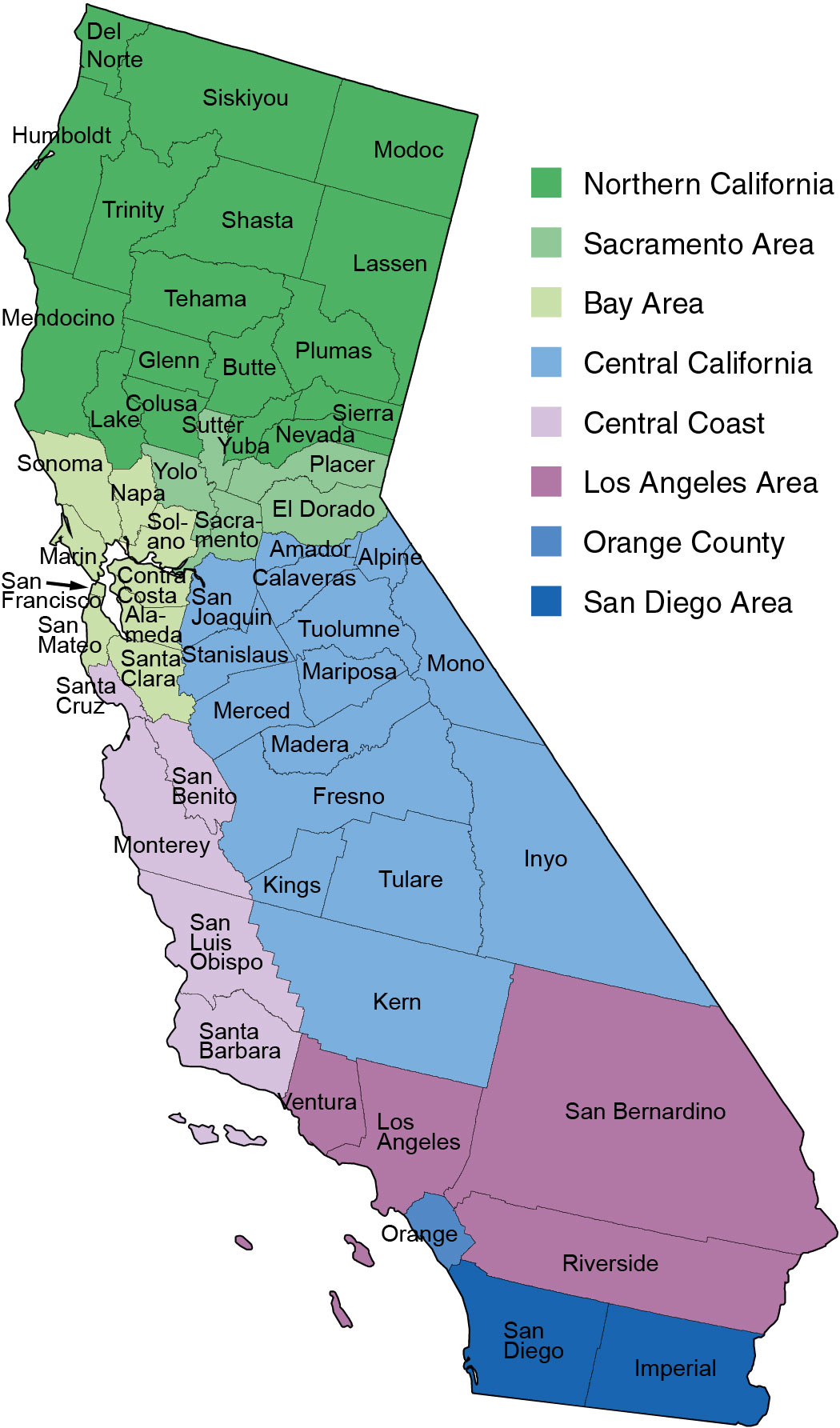

The Career Technical Education Pathways Initiative aims to engage learning institutions at all levels in improving linkages, increasing readiness of secondary students for postsecondary education, and increasing student success and training in postsecondary education. Grants provided through the program help in the development of local and regional career technical education pathway systems. For example, the Bay Area Community College Consortium is developing new curricula with eight colleges and 28 manufacturing industry partners to strengthen the alignment of training programs with regional industry needs. It has also created work-based learning opportunities at six Bay Area companies.

Strengthening for Tomorrow

Initiate apprenticeship programs to build skills for new workers and to train those that are changing fields.

Corporate apprenticeship programs can be used to draw younger workers into the manufacturing field in California. By combining classroom training with on-the-job experience, the costs of training new employees for manufacturing skills can be split between the educational system and industry. Germany employs the best practice apprenticeship model under which two-thirds of the country’s manufacturing workers are trained through partnerships among companies, vocational schools, and trade guilds. Germany’s system is part of the reason the country’s youth unemployment rate is below 8 percent, less than half of the rate in the US. Switzerland offers another successful example of public-private cooperation to support manufacturing and other skills development through apprenticeships.

Domestically, the Department of Labor supports public-private partnerships that establish apprenticeship programs in advanced manufacturing. At the state level, South Carolina has been able to stimulate apprenticeships through a $1,000 tax credit per year per apprentice. A similar initiative in California can be tailored to small and medium manufacturing enterprises that cannot otherwise afford the in-house training programs that will be needed to bridge skill and generational gaps going forward.

Support state-funded technical education programs through sustained funding connected to metrics for effectiveness.

The 2015–2016 California state budget established the Career Technical Education Incentive Grant Program to spur partnerships between school districts, colleges, and businesses. The budget provides $400 million, $300 million, and $200 million in each of the next three years, respectively, for competitive grants. These grants would require a dollar-for-dollar match and proof of effectiveness across a range of outcomes such as graduation rates, course completion rates, and the number of students receiving industry credentials. Additionally, the 2015–2016 California state budget extended the Career Technical Pathways Initiative by one year, which will sustain a program that has been in existence since 2005 and can be instrumental in promoting advanced manufacturing career exploration for community college students. Attention should also be paid to the sustainability of these programs after state funding expires.

Adopt a statewide certification for advanced manufacturing skills across strategically selected schools.

California can develop a manufacturing certification model that allows students to sequence credentials over time to build comprehensive advanced manufacturing skills. These certifications should range from machining and tool and die making to maintenance technician and quality control skills. They should also be compatible with the National Association of Manufacturers’ skills certification system, so that the credential can be transferred to work in other states. Designating strategic community colleges as “manufacturing schools” could also sharpen the manufacturing focus across the state and give regional industry participants a more streamlined means to participate in curriculum development and to recruit future workers.

Pursue higher goals for incorporating STEM education and its associated career pathways into curricula for elementary and high schools.

Educational objectives in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) continue to be high priorities in school districts around the state. Programs that bring robotics, machining, and other applied technologies into K–12 classrooms can begin to fill the talent pipelines needed for advanced manufacturing in the state. By reaching students at an earlier age, these types of programs can provide awareness of the options available to students who may not wish to pursue a four-year degree, and these programs can increase the knowledge and appeal of manufacturing careers.